Acknowledgments

The research team for this report was led by Jamison Henninger and Mandy McCleary, who also contributed to the writing, research, and analysis, along with team members Jaysen Ensor, Tawheeda Wahabzada, and Raquel Fontes. Insights and editorial support were given by Eric Swanson, Francesca Perucci, Lorenz Noe, and Shaida Badiee. We also thank Amelia Pittman for her work on graphics.

Finally, we extend our sincere thanks to Wellcome for their generous financial support, which makes this work possible.

Executive Summary

In early 2025, an abrupt withdrawal of development assistance—driven by pauses in foreign aid and wider donor retrenchment—triggered a systemic shock to global health data systems. These systems, already reliant on a concentrated set of bilateral and multilateral funders for surveys, civil registration and vital statistics (CRVS), health management information systems (HMIS), and disease surveillance, now face immediate interruptions and heightened medium-term risks to data continuity, quality, openness, and use.

This report synthesizes early disclosures from major agencies, data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development / Development Assistance Committee (OECD/DAC), and a rapid assessment survey covering more than half of national statistical offices (NSOs). Evidence on philanthropic and domestic financing is incomplete, and survey nonresponse may introduce bias, but convergent signals show broad exposure. Three unknowns will shape the next 12–18 months: the duration of donor withdrawals, the degree of philanthropic bridging, and the extent of government backfilling to protect core functions.

Key Findings

Scale of reductions: Funding contractions and spending freezes are forcing difficult trade-offs across surveys, CRVS, HMIS operations, and disease surveillance.

Core survey shocks: The Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) and Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS)—cornerstones for Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) monitoring and policy—were disrupted mid-cycle, with some rounds delayed or only partially completed.

Administrative and surveillance strain: CRVS upgrades and HMIS upkeep slowed or stalled, while vertical surveillance networks (including HIV, tuberculosis, malaria, and measles/rubella laboratories) lost funding and technical support.

Capacity erosion: Layoffs and hiring freezes reduced hands-on technical assistance to NSOs, increasing risks of method drift, maintenance gaps, and quality decline.

Areas most exposed: Highly data-dependent fields—infectious disease, climate and health, and discovery research—are particularly vulnerable to breaks in standardized, continuous data streams.

Risk Outlook (12-18 months)

Continuity: Delays and potential breaks in time series threaten trend analysis and SDG reporting; severity depends on reliance on external funds and the speed of bridging finance.

Modeling and research: Impaired flows of comparable data weaken disease modeling and slow basic and cohort research, with disproportionate effects in vulnerable settings.

Governance and access: Without shared standards and timely publication, comparability and public use will deteriorate.

Early Responses

Stopgaps: Targeted domestic reallocations and short-term philanthropic grants are preventing immediate collapse of selected surveys and services.

Preservation efforts: Civil-society and academic partners are archiving datasets and documentation to safeguard access and continuity.

Coordination starts: Governments and multilaterals are piloting nationally owned survey programs and exploring diversified financing and standards through UN-anchored taskforces.

Next Steps

Country leadership and governance with multi-year financing to align partners behind national plans and route predictable support through country systems to spread risk.

Build and retain core statistical capacity in permanent national teams with structured regional support.

Protect continuity and comparability through shared standards and open access with advance release calendars and metadata, and timely publication of data.

Use public monitoring to align financing, production, and access by pooling country plans, release calendars, and funder commitments to match demand with supply and reveal gaps.

Section 1: Introduction

The abrupt withdrawal of development assistance by many large donors in early 2025 marks a potential turning point for global health data systems (Apaeagyi, et al. 2025). For decades, these systems relied heavily on a small group of bilateral and multilateral donors to sustain core functions, including monitoring disease, planning health services, and guiding research (PARIS21 2024). Understanding the consequences of this disruption is essential to shaping future strategies and sustaining the systems that enable evidence-based health policy and research.

This report begins with an overview of the health data system and its pre-existing vulnerabilities. It then examines the reductions in funding and assesses the broader risks these changes pose to the global health data system in the next 12–18 months. Subsequent sections consider how these disruptions affect global data capacity, review the immediate and longer-term responses of major actors, and conclude by identifying remaining gaps and recommending actions to restore and strengthen health data systems in the years ahead.

The analysis in this report draws on early agency disclosures, data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development / Development Assistance Committee (OECD/DAC), and a recently launched “National Statistical Offices’ Experience with the Sustainability of Demographic and Health Statistics through Household Surveys – Report of the Survey of National Statistical Offices: Sustaining Survey Data Production, Dissemination and Use – A Rapid Assessment of Impact and Resilience Amid Funding Gaps and Disruptions” (hereafter referred to as “Rapid Assessment of NSOs”).[1] This assessment was conducted by the Task Force on Sustainable Demographic and Health Statistics through Surveys of the Inter-Secretariat Working Group on Household Surveys (ISWGHS), in collaboration with the Inter-Agency and Expert Group on Sustainable Development Goal Indicators (IAEG-SDGs), UN Women, and the World Bank. The assessment collected responses from over half of NSOs worldwide, providing one of the few systematic views of how statistical offices themselves are experiencing funding reductions. Each source has gaps—philanthropic and domestic public financing are only partially reported—and some values may be revised. Nonresponse to the Rapid Assessment may also introduce bias, along with other limitations outlined in the full report. We treat the survey evidence as a directional signal and corroborate it with independent sources throughout. Interpretation hinges on three unknowns tracked in this report: the duration of withdrawals, the extent of philanthropic fill-in, and whether governments intervene to protect core statistical functions.

Section 2: Background

The reductions in development assistance place the global health data system under unprecedented pressure. This section outlines how this system functions, what enables it to succeed, and where it was already vulnerable. These details are essential for understanding the implications of funding cuts on global health data systems and the broader international data ecosystem.

2.1 Health Data Systems

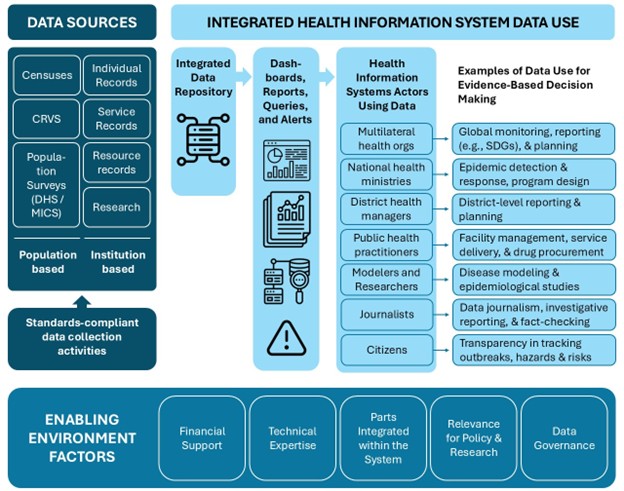

At the center of this disruption is the complex, integrated health data system, as shown in Figure 1. Data inputs for the health data system come from population-based sources such as censuses and surveys and institution-based sources such as individual records from health facilities. These data sources are integrated into data repositories that are then aggregated for dashboards and reports.

Institution-based integration and aggregation at the country or regional health department level are frequently done through health management information systems (HMIS) that are designed for routine data collection, management, and analysis. The District Health Information Software 2 (DHIS2) is the most widely used open-source HMIS system used globally. Population-based data are compiled by national statistical offices (NSOs) for censuses and surveys. Civil registration and vital statistics (CRVS) are managed jointly by several government agencies. Aggregated data can then be shared and used by local and global actors for evidence-based policies.

Five enabling factors are needed for a successful health data system: (1) sustained financial support; (2) technical expertise to create and maintain high-quality and usable data systems; (3) effective integration of the data sources into the system; (4) clear links between data and policy and research needs; and (5) sound data governance that ensures both security and availability of data. These enabling factors ensure that data can be successfully integrated into repositories and used by actors as evidence for decision-making.

Figure 1 The health data system

Download the Health Data System diagram.

Source: Open Data Watch (ODW) adaptation of Fig. 12, Health Information Metrics and WHO Framework and Standards for Country Health Information Systems.

Figure acronyms: CRVS=civil registration and vital statistics, DHS=Demographic and Health Surveys, MICS=Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys, SDGs=Sustainable Development Goals.

2.2 Underlying Systemic Weaknesses

Even before 2025, this infrastructure showed signs of strain. In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), data collection relied on technical expertise and financial support from bilateral, philanthropic, and multilateral channels (PARIS21 2024). Weak coordination limited the effectiveness of investments, while fiscal pressures narrowed governments’ capacity to step in when donors withdrew (UN DESA 2025b). For example, without external support, some HMIS have returned to or decided to keep inefficient but easier to implement systems, such as paper records (WHO n.d.-c). Declining donor commitments have compounded these challenges, with major reductions in official development assistance (ODA) for health and health data, including a 6 percent decrease in disbursements between 2023 and 2024, further straining the system even before 2025 (Huckstep, et al. 2025, OECD 2025).

Broader fiscal pressures have reinforced the fragility of health data systems. The global financing gap for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) widened from an estimated $2.5 trillion in 2019 to roughly $4 trillion annually in 2023 (UN DESA 2025b), narrowing the fiscal space for LMICs to invest in health statistical capacity and data infrastructure. The COVID-19 pandemic compounded these pressures, diverting resources away from data operations, delaying census rounds, and forcing costlier methods such as remote training and contactless enumeration (World Bank 2020).

Budgetary constraints in global agencies compounded the problems. For example, the World Health Organization (WHO) receives funding from two sources: countries’ membership dues and voluntary contributions. More than four-fifths of WHO’s program budget depends on voluntary contributions from countries, philanthropic organizations, the private sector, United Nations (UN) organizations, and intergovernmental organizations. This dependence on voluntary contributions leaves core programs highly vulnerable to donor withdrawals (WHO 2025b).

Due to the fragile funding system for global data, health data systems faced persistent gaps in data and data quality that they struggled to fill, even before 2025. As of 2020, less than a sixth (12 of 74) assessed HMIS met “good” data quality standards, with $120 million [2] required annually to upgrade the remainder (Open Data Watch, Data2X n.d.). Between 2016 and 2020, just 30 percent of essential SDG health-related surveys were completed in International Development Association-eligible countries, with an estimated additional $404 million needed to fill that gap. Based on an analysis by Open Data Watch drawing on work by the World Bank and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), the 2020 census round faced a significant global shortfall in funding, leaving roughly 30 percent of the world’s population without census coverage (UN ECOSOC 2024, UN ECOSOC 2025).

2.3 Reductions in Funding in January 2025

On January 20, 2025, the U.S. administration issued Executive Order 14169, pausing all foreign assistance (Executive Office of the President 2025). Within weeks, more than 90 percent of United States Agency for International Development (USAID) contracts were terminated, including $12.7 billion tied to health programs and data systems (Kates, Rouw and Oum 2025).[3] Additional reductions by European governments and multilateral organizations in 2025 compounded the crisis (Huckstep, et al. 2025). According to OECD estimates, net ODA is estimated to decrease by 9 to 17 percent, with even higher reductions to ODA for health and health data of 14 to 29 percent between 2024 and 2025.

As a result, according to the Rapid Assessment of NSOs, the majority of NSOs in LMICs (69 percent) reported reductions to their budgets in 2025.[4] Of the NSOs experiencing reductions to their budgets, most (80 percent) cited reductions in funding from international organizations as one of the sources (ISWGHS 2025a), followed by national government (71 percent) and bilateral and private foundations (40 percent).[5] Around three in ten impacted NSOs (29 percent) reported that their total budgets, including for surveys on demographics and health, had been reduced by more than 25 percent (ISWGHS 2025a).

Health data in LMICs are dependent on a small group of donors: the top five donors provided 60% of global ODA for health data between 2018-2022, with the US contributing nearly 27 percent (ODW analysis based on PRESS 2024). This concentration, coupled with large data gaps and widespread external reliance for funding, created a compounding crisis. These pre-existing weaknesses meant that when major donors abruptly reduced funding in 2025, the health data system was already fragile and ill-prepared to absorb the shock. The next section examines the scale and distribution of these reductions, highlighting which regions and programs are most affected.

Section 3: Reductions in Global Funding for Health

Global health programs were disproportionately affected by reductions in funding in 2025. According to The Lancet, the United States, which was the largest funder for development assistance for health (DAH), previously funded 20–25 percent of DAH on average ($13 billion in 2024) but is now predicted to fund only around 7.5 percent of DAH ($5 billion) (Apaeagyi, et al. 2025). Many of the terminated U.S. awards included general support for health data and statistics as well as for monitoring specific health areas, such as polio vaccination, maternal and child health, infectious disease rates, HIV treatment, and family planning (Kates, Wexler, et al. 2025).

Table 1 Organizational Funding Cuts from 2024-2025

| Multilateral Organization | Percentage Reduction | Annual Amount Reduced |

| Global Fund | 11 percent (grants)1 | $1.43 billion1 |

| UNICEF | 20 percent plus2 | $1.7 billion*,2 |

| Gavi | 21 percent3 | ~$2.5 billion (funding gap for 2026-2030)3 |

| WHO | 21 percent4 | $1.1 billion4 |

| UNFPA | 26 percent*,5 | $335 million6 |

| Global Polio Eradication Initiative | 40 percent7 | $2.3 billion (funding gap over 5 years)7 |

| Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS | 50 percent8 | $105 million*,9 |

* Estimated using either the percentage reduction and previous annual budget or known reduction and previous annual budget to produce the percentage

Sources: 1 (Green 2025); 2 (Nichols 2025); 3 (Keller, et al. 2025); 4 (Cullinan 2025); 5 (UNFPA n.d.); 6 (UN 2025); 7 (Shetty and Anderson 2025); 8 (Bartlett 2025); 9 (UNAIDS 2025b)

A significant portion of the U.S. DAH funding supported multilateral organizations’ health and data programs. As shown in Table 1, the Global Fund, UNICEF, Gavi, WHO, UNFPA, the Global Polio Eradication Initiative, and the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), saw budget reductions between 10 and 50 percent. Among these, the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (40 percent reduction) and UNAIDS (50 percent reduction) were the hardest hit. In addition to these cuts, many bilateral programs focused on global health data had their funding reduced.

The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation’s (IHME) report, Financing Global Health 2025, projects that, amid steep declines in DAH, the sharpest reductions in health spending will occur in sub-Saharan Africa. Countries most at risk include Malawi, the Gambia, Lesotho, and Mozambique (Apaeagyei, Bariş and Dieleman 2025). These regional trends provide important context for the country examples that follow, highlighting disruptions in countries central to global health and data system development.

NigeriaUSAID spent US $463.8 million on health in Nigeria in 2024, including US $32 million for nutrition. When USAID funding was cut, clinics throughout the country lost access to their logins, software, and data. Due to the abrupt and immediate cancellation of the funds, patient records were not transferred beforehand. Nigeria has high levels of malnutrition, and the loss of information and pre-existing weaknesses in the health infrastructure exacerbated this issue. It is estimated 19,000 additional child deaths from malnutrition will occur due to these reductions (Osayi n.d., Flaxman, Lutze and Bowman 2025). |

The United States has historically provided significant funding for HMIS, household surveys, population censuses, and disease surveillance networks. The sudden contraction in funding did not leave time for orderly transitions, and interim funding from other actors has thus far been limited in both scale and speed. Flagship programs such as the DHS, funded largely by USAID, the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS), funded by UNICEF, and civil registration and vital statistics (CRVS), whose funding varies but includes large investments from the Global Fund, were all affected, alongside vertical disease surveillance programs managed by WHO, UNAIDS, and Gavi. The abrupt halt of these programs, the subsequent reductions in NSOs’ budgets, and the dependence of some countries on a small group of donors, creates uncertainty about how to continue to produce the health data that are essential for policymaking.

3.1 The Change to the DHS Program

For nearly four decades, the DHS Program has been a cornerstone of global health data. It provides high-quality, comparable information on fertility, maternal health, child health, nutrition, HIV, malaria, water, sanitation, and other indicators, many of which are difficult to capture in low-resource settings. DHS surveys have been conducted in over 90 countries worldwide since the program’s inception (DHS Program n.d.). The DHS Program has influenced both national and global planning, evaluation, and policy decisions in at least 30 countries since 2015 (ISWGHS 2025a). Data from the DHS Program can be used for up to 39 SDG indicators (UN DESA 2025a). The vast majority of NSOs that have conducted a DHS survey since 2015 reported using DHS data for health policy formation (93 percent), family planning and reproductive health strategies (93 percent), and children’s health and nutrition policies (90 percent) (ISWGHS 2025a).[6] The breadth and quality of DHS data and their impact on policies make the program indispensable to the global health data ecosystem (Dattani 2025).

The DHS Program was funded primarily by USAID and was one of the 90 percent of programs whose contracts were cancelled in 2025. Philanthropic donors provided temporary funding to complete ongoing survey rounds and keep the program running for up to three more years, though its longer-term sustainability remains uncertain. The interruptions to the DHS Program occurred mid-cycle, leaving dozens of surveys in limbo, with uncertain funding and technical support to continue. As of March 31, 2025, over 22 DHS, Malaria Indicator Survey, and Service Provision Assessment rounds, all run by the DHS Program, were affected (Khaki, et al. 2025).[7]

These interruptions risk creating multi-year gaps in nationally representative health data. The gaps in health data are likely to impair resource allocation, weaken the monitoring of progress toward the SDGs, and complicate compliance with international reporting obligations. Emergency funding has made it possible to finish ongoing survey rounds, but the longer-term sustainability of the DHS Program remains unclear.

3.2 The Effect on CRVS and Health Administrative Data Systems

CRVS systems record births, marriages, divorces, and deaths, providing legal identity and continuous demographic data. They support public health planning, resource allocation, and rights protection. However, using data from DHS, MICS, and other health surveys, UNICEF estimated that approximately 150 million children under five—about one in five—remained unregistered as of 2024 (UNICEF 2024).

KenyaKenya’s health data system faced major disruptions following reductions in U.S. government funding and support. The Kenya Electronic Medical Records system, for example, became temporarily inoperative, disrupting procedures and tracking systems at health facilities, which were briefly forced to use paper-based data management. As a result, Kenya has shifted to host its digital health systems, including Kenya Health Information System, Kenya Master Health Facility List, and KenyaEMR, to locally-hosted servers, emphasizing the importance of national ownership for health systems (Ndege 2025, WHO 2025a). The disruptions to administrative health data systems increased the risk of data loss, increased security breaches, and reduced capacity for patient tracking, care, and public health reporting (Shikanda 2025). |

CRVS systems are financed by a mix of multilateral and bilateral sources. The International Development Association (IDA) and the Inter-American Development Bank alone account for half of all financing for CRVS systems in recent years, underscoring the value of multilateral pooling of funds. At the same time, a heavy reliance on few donors and a few large projects leaves financing for CRVS systems vulnerable to disruption.

Although financing for CRVS systems has increased in recent years, this was not enough to fill the amount required to build strong systems. Death registration, in particular, receives much less financing than birth registration systems, which can impact the completeness of health information systems due to missing cause of death data or simply death prevalence (Open Data Watch 2025).

The reductions in funding have stalled or slowed CRVS digitization projects in several countries. In Ethiopia, program suspensions disrupted data collection and retention of trained personnel, with knock-on effects for health service reporting and disease surveillance (ACAPS 2025).

The U.S. withdrawal from Gavi in mid-2025 further constrained vaccine-linked surveillance activities that often integrate with CRVS and HMIS platforms (KFF 2025). These combined funding losses risk widening existing coverage gaps and reducing the accuracy of mortality and population data in low-income settings.

In addition to improved financing for disrupted CRVS programs, better integration of support for CRVS with digital public infrastructure plans and legal identity initiatives would improve the sustainability of financing for CRVS systems.

3.3 The Interruption to MICS

Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS), led by UNICEF, are the primary source of internationally comparable data, contributing to almost 40 SDGs, about children and women in at least 119 LMICs (UNICEF n.d.-a). They supply critical information on health, education, nutrition, child protection, and water and sanitation, especially in contexts lacking recent census data or robust administrative records.

Before 2025, MICS operations relied on a mix of UNICEF core resources, bilateral donor funding, and contributions from philanthropic partners (UNICEF n.d.-b, UNICEF n.d.-c). Funding reductions in preceding years, including the withdrawal of major philanthropic donors, had already narrowed the program scope and increased the program’s vulnerability to shocks.

Although MICS represent only part of UNICEF’s work, UNICEF’s dependence on flexible and donor-linked funding makes it particularly sensitive to such reductions. Registry data from August 2025 showed that 52 MICS surveys were in progress. At least 16 were already facing delays and problems with finalizing the results due to capacity constraints after funding reductions (UNICEF n.d.-a). In addition, the MICS and DHS Programs have coordinated efforts to ensure the generation of complementary results and to avoid duplication of efforts (DHS Program 2015). However, this means that interruptions to either program limit the complete production of data and the holistic understanding of children’s and women’s health for potentially a few years. This data gap would in turn limit the monitoring of SDG progress and country responses to emerging needs — from shocks such as epidemics or climate crises to urgent child health, nutrition, and education challenges.

3.4 The Uncertainty for Vertical Health and Disease Surveillance Programs

Vertical health programs and disease-specific surveillance systems deliver targeted interventions for specific diseases and generate high-quality, standardized data on priority diseases. Analysis of the USAID termination list shows the breadth of the reductions in funding by sub-sector. Maternal and child health and nutrition each saw 86 percent of awards terminated, followed by family planning/reproductive health (85 percent), malaria (80 percent), tuberculosis (79 percent), and HIV/AIDS (71 percent) (Kates, Wexler, et al. 2025). Without USAID, health data systems that cover these illnesses are seeing reductions in program coverage, and some programs are at risk of being terminated.

In 2024, UNAIDS estimated that US $18.7 billion was available for HIV responses in LMICs, with donor governments contributing about 44 percent (Wexler, Kates and Lief 2025). The United States, historically the largest bilateral donor, played a critical role in sustaining HIV testing, treatment monitoring, and incidence surveillance. Even countries that did not rely on U.S. funding for most of their HIV testing, treatment, and surveillance programs are seeing setbacks. For example, South Africa provided 83 percent of the funding for its HIV programs (Long, et al. 2023). However, due to reductions and uncertainty in funding, South Africa reported an 11.4 percent year-on-year decline in viral load testing in April 2025, with even sharper drops among young people and pregnant women (Peyton 2025). Countries with fewer resources are likely to have seen larger reductions in support and greater interruptions to health services and data reporting.

Reductions in funding limit the effectiveness of programs focused on disease surveillance, service delivery, and international reporting on diseases. In March 2025, the WHO Director-General warned that the global measles and rubella laboratory network—comprising more than 700 laboratories and funded solely by the United States, which provides surveillance infrastructure—was on the brink of closure at a time when there were measles outbreaks in North America, Europe, and Africa (WHO 2025c). Gavi, which provides vaccine delivery and integrated disease surveillance, will not be able to continue at the same service provision level (KFF 2025).

Surveillance platforms are important sources of timely and independent data on global health, and they face direct and indirect risks. For example, the Data for Accountability, Transparency and Impact Monitoring (DATIM) platform run by the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) that tracked HIV/ AIDS data over time was terminated.[8] The closure of this program will make tracking and responding to HIV/AIDS more challenging. Certain platforms that were not funded by USAID, such as IHME’s platform, still depend on national surveys, HMIS, and vertical program data streams that are now disrupted or at risk of degradation (IHME n.d.). The WHO’s non-communicable disease surveillance platform has not announced changes yet, but it is at risk of seeing its funding reduced, given the overall reductions to the WHO’s budget (WHO n.d.-a). The cumulative effect is a reduction in the timeliness, coverage, and quality of disease surveillance, increasing the likelihood of delayed outbreak detection and weakened public health response capacity.

Section 4: Assessment of Risks Over the Next 12–18 Months

The reductions and changes in financing for global health data and statistics in 2025 have exacerbated existing sources of risk within global and national health data systems. In this report, “risk” refers to the effect of uncertainty on objectives for health data (continuity, quality, openness, and use), and a “risk event” is the occurrence or change of specific circumstances—such as a funding suspension, platform shutdown, or loss of key staff—that can trigger consequences. The impact of any risk event varies by context and by the strength of the enabling environment for sustained data collection. Recent funding changes have already triggered several risk events and interrupted planning and collection cycles; many direct consequences have occurred in the months following the largest funding shifts. Appendix A summarizes risk sources, risk events, direct consequences, impact, and mitigation measures.

In addition to direct consequences, funding changes create indirect effects that unfold over time. This section examines how known risk events are producing (or could produce) direct and indirect consequences and how mitigation can reduce their impact. The overall scale of risk still hinges on uncertain factors: the duration of donor withdrawals, the extent of philanthropic bridging, and the degree to which governments step in to protect core functions.

4.1 Trend and Continuity Interruptions

The reduction in global health funding directly impacts the sustainability of health surveys and administrative data by disrupting the production cycles of these data. These disruptions impact data continuity and efforts to track trends over time. For example, 97 percent of NSOs that had conducted a DHS survey since 2015 reported that their main objectives in conducting a DHS survey were to use the data for SDG monitoring and reporting , for evidence-based policies , to analyze population trends , and to monitor health indicators and outcomes (ISWGHS 2025a). Data from the DHS program are used for 39 global SDG indicators, including 11 under Goal 3 (Good Health and Well-Being) and 6 under Goal 5 (Gender Equality). For several indicators—such as contraceptive use (SDG 5.6.1) and experiences of sexual violence (SDG 16.2.3)—over 70 percent of data points come from DHS sources (UNSD 2025). When DHS data are interrupted, global and national efforts to identify health trends and create policies using this information will be impacted.

The changes in funding directly affected reoccurring survey programs, like the DHS and MICS Programs (Khaki, et al. 2025). However, most of these programs have temporary measures in place to continue activities, so the effect on existing time series is of low severity in the short run, with the primary challenges being delays in data production and disruptions to processes. For example, the Rapid Assessment of NSOs showed that over half of NSOs (57 percent) that had conducted a DHS survey since 2015 reported encountering or anticipating delays—which may make the data less relevant and useful—and reduced access to external expertise (37 percent), which highlights concerns over countries’ immediate ability to produce high-quality health data without support, depending on the long-term future of the DHS Program (ISWGHS 2025a).

The funding reductions also impact disease surveillance, CRVS, and health administrative systems. For disease surveillance, HIV/AIDS monitoring efforts are being impacted more severely due to the termination of DATIM, which was a crucial tool for monitoring. The interruptions to data collection will be of high severity in countries like Kenya and Nigeria, where high donor reliance halted access to health data systems (Powell, Lagomarsino and Melamed 2025, Osayi n.d.). However, some proposed mitigation efforts, such as incorporating data collection previously done through surveys into existing administrative systems and routine reporting channels, may reduce the severity of the impact on trend comparability and continuity. Whether data collection can resume without losing trend comparability depends on how long funding interruptions persist, how quickly technical support is restored, and how countries respond and build workaround solutions.

4.2 Loss of Access to Technical Support

Health data systems rely on specialized expertise—from questionnaire design and survey methods to statistics, data management, secure processing, and communication. Recent funding disruptions have triggered major layoffs, including over 95 percent of USAID staff (Murphy 2025), a proposed 30 percent of mid-level staff within WHO (Fletcher 2025), and 25 percent of U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) global health staff (Tanis 2025). Public reporting does not consistently distinguish in-country versus headquarters positions, an uncertainty that matters for long-term country capacity.

Many of the institutions affected provided hands-on technical support to national health data systems. Layoffs are likely to have a medium-severity impact over the next 12–18 months as responsibilities shift, new points of contact are named, and remaining staff take on heavier workloads. In response to the cuts, many NSOs signaled their need for technical assistance (57 percent) and capacity building (47 percent) to produce health data (ISWGHS 2025a). With external expertise in flux, NSOs risk losing capacity for core functions such as survey design, data processing, and system maintenance—undermining operational reliability.

The severity of the impact on technical capabilities will grow gradually over the next year and a half, first as staff face burnout with constricted technical support and capacity, and databases and platforms fall into disrepair since maintenance is not prioritized. The weakened technical capacity of national statistical systems is likely to limit donor-dependent countries’ maintenance of databases and HMIS, leading to data gaps, declining system reliability, and slower recovery from disruptions.

To address short-term constraints in technical capacity, some global health implementers with DHS experience could provide limited, stopgap technical assistance where they retain active non-USAID funding (e.g., from foundations or UN agencies). However, most subcontractors have been significantly affected by USAID reductions, and their alternative funding is insufficient to replace the scale of technical support previously available. As a result, any interim assistance would need to be carefully prioritized and paired with medium-term investments in country-led capacity.

The medium-term impact remains uncertain and hinges on whether stopgap technical assistance scales quickly enough to prevent system drift and data quality degradation, how countries address these issues, and create innovative solutions.

4.3 Impaired Disease Modeling

Disease modeling assesses the current and future risks of diseases and forecasts the spread of diseases, helping researchers and public health practitioners prevent or mitigate the spread of disease. These disease models often benefit from continuous survey and administrative data inputs (Fisher, et al. 2020, Cole, et al. 2020). As data streams for models are interrupted or degraded, they lose accuracy and relevancy and delay the detection of emerging threats, response, and general policymaking. As a result, impaired disease modeling limits the efficacy of national surveillance systems and global research networks.

The effect on disease modeling is of medium severity in the next 12 months due to interruptions and delays to programs, the loss of technical capacity at major multilateral organizations, and reductions in the structures used to coordinate data collection and access. Data collection and modeling in critical and vulnerable areas are likely to see greater impacts from changes to funding.

However, some potential mitigation efforts are available, including the implementation and use of rapid risk assessments. Rapid risk assessments can provide public health “risk managers with a timely and evidence-based assessment of the risk and associated levels of uncertainty upon which to base risk management, surveillance and research recommendations” (Anand, et al. 2024). The WHO uses rapid risk assessments to characterize disease risk during public health emergencies at the national, regional, and global levels (WHO n.d.-b). Done well, the data from rapid risk assessments could be used as an interim, non-traditional, and non-official source of data for disease modeling, and to capture emerging health threats

4.4 Challenges to Basic Research

Basic research is heavily reliant on government funding, as private industries are hesitant to invest in research and development without a clear return on investment (Leptin 2023). Basic research is currently beset by interruptions to funding and disruptions to data systems, including survey and administrative health data, that are used to identify areas of further research and to examine the effects of interventions over time (Community Commons n.d.). Basic research also relies on the same health infrastructure as health data systems—trained personnel, coordinated systems, HMIS platforms—and is therefore prone to the same vulnerabilities in these areas.

These three factors, taken together, will have a medium severity impact on the continuation and quality of basic health research. Time series from reoccurring surveys have been interrupted, which has led to delays, projects to improve accessibility have been delayed, and changing technical expertise may mean that standards are not as strictly adhered to, which has implications for data quality. Some basic research projects funded by bilateral donors, especially those focusing on climate change, women, and minority populations, have lost all or most of their funding, which means there will be a high severity impact to basic research in those areas (Outright International 2025, Welz 2025). Potential mitigation efforts include new and innovative sources of funding, especially from the private sector, national governments, and bilateral donors, which may sustain basic research.

Section 5: Impacts on Key Program Areas

Three key program areas—climate and health, infectious disease, and discovery research—rely on strong data ecosystems that support early-warning and exposure-risk analysis (climate and health), surveillance and outbreak modeling (infectious disease), and long-term cohort and basic science studies (discovery research).These areas are widely shared priorities across donors, governments, and research networks; they are highly data-dependent and among the most exposed to recent funding shifts, so they serve as practical lenses on system-wide impacts. This section examines the effects of the changes in funding for global health data and statistics by program area and then assesses implications for policy, operations, and research.

The analysis draws primarily on the Partner Report on Support to Statistics (PRESS), which tracks official development assistance (ODA) to data and statistics in low- and middle-income countries and includes a limited subset of private foundation disbursements. PRESS does not capture domestic government spending and only partially reflects broader philanthropic flows. Figures should therefore be read as directional estimates and are triangulated with program reports and agency communications cited in each subsection.

5.1 Overview of ODA for Health Data by Key Program Area

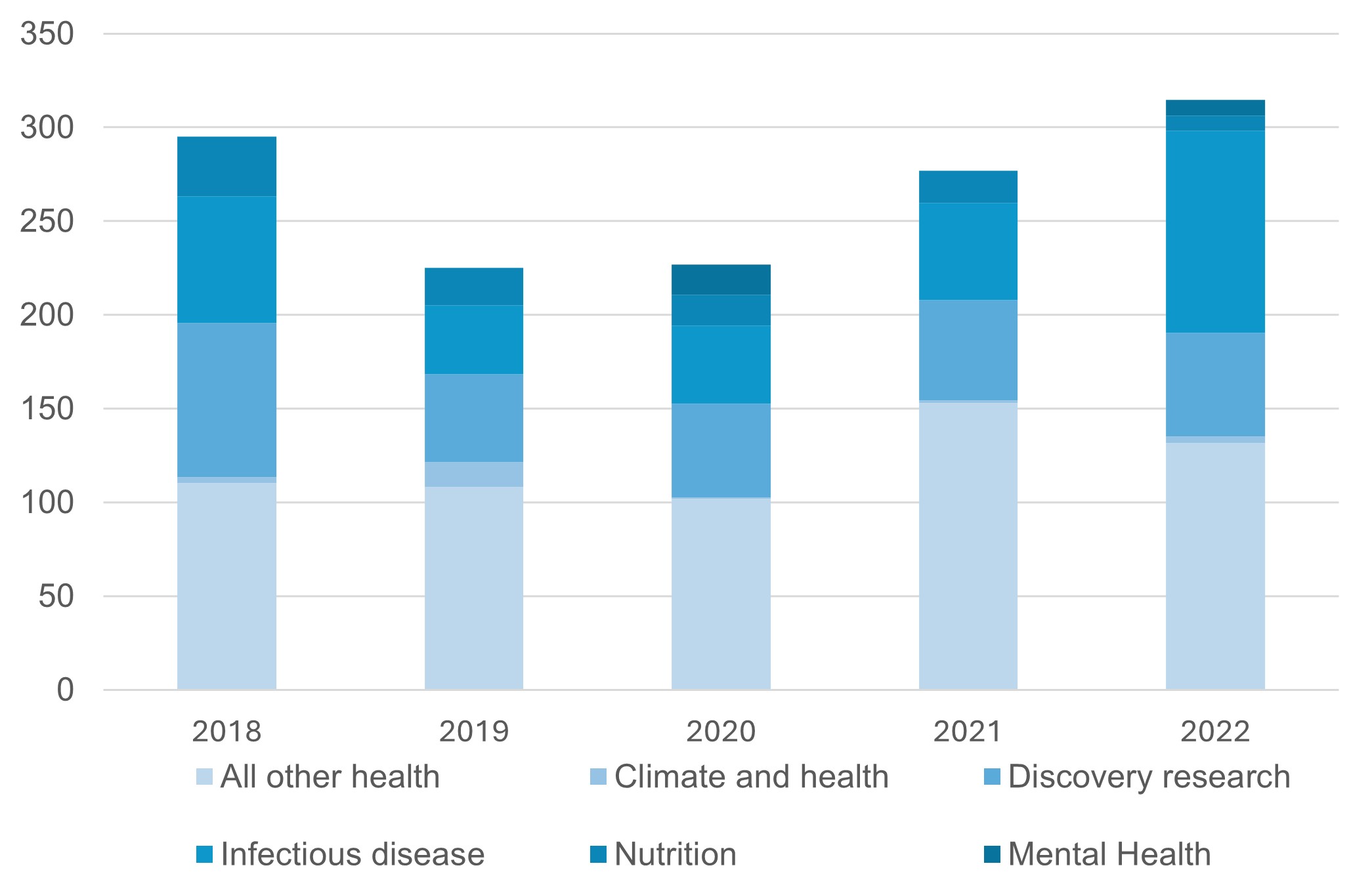

PRESS, produced annually by PARIS21, monitors disbursements of private foundation and ODA for data and statistics.[9] Following a methodology outlined in Appendix B, PRESS data were used to develop Figure 2 on ODA for health data and statistics between 2018 and 2022, across key program areas: Climate and health, discovery research, infectious disease, nutrition, and mental health. Nutrition is included because climate change has a significant impact on nutrition, and sometimes it may be more useful to look at the combined disbursements for climate and nutrition (Sparling, et al. 2024). PRESS data from 2018 through 2022 showed chronically low levels of disbursements for climate and health and mental health, decreased funding for discovery research disbursements,[10] and increased disbursements for infectious diseases, from a low in 2019.

Figure 2 Amount of ODA disbursements (million USD) for health data and statistics by program area between 2018 and 2022 [11]

Million USD

Figure data available here.

Source: ODW analysis based on PRESS 2024.

As detailed in Sections 1 and 2, because of recent changes in funding for health, it is anticipated that ODA for health data will also be lower in 2024 and much lower in 2025. Reductions to data infrastructure and technical capacity will further limit the continuity and reliability of data used across these areas.

5.2 Infectious Disease

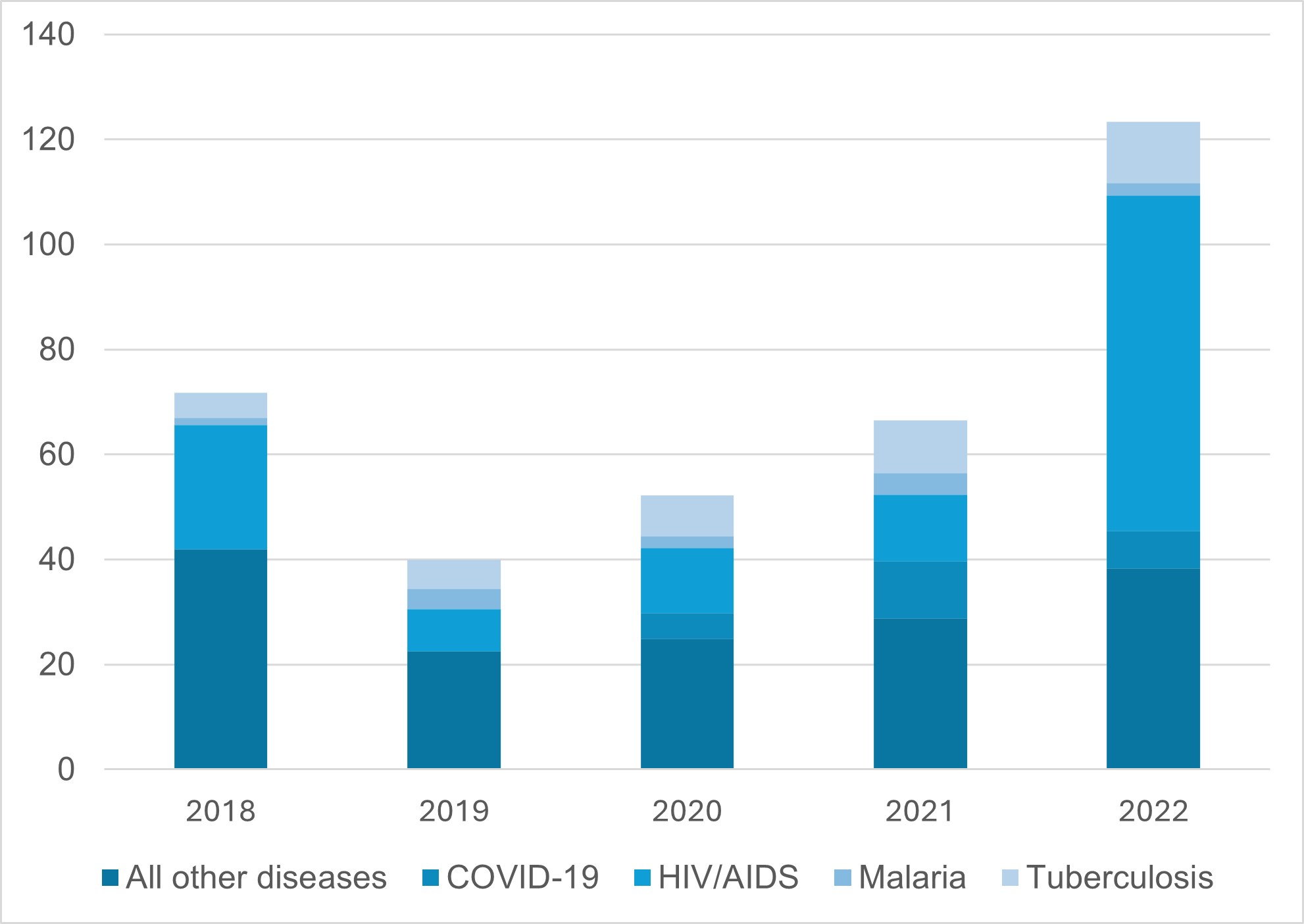

Programs focused on infectious disease supports surveillance, modeling, and intervention research for tuberculosis (TB), HIV, malaria, and emerging epidemic threats, especially in LMICs in Africa and South and Southeast Asia. The relevant risks include trend and continuity interruptions and impaired disease modeling. According to the PRESS analysis, of the US $306 million ODA for infectious disease statistics between 2018 and 2022, 43 percent (US $132,893,035) went to sub-Saharan African countries. Similarly, 44 percent (US $134,944,754) went to least developed countries (LDCs). As seen in Figure 3, when ODA for infectious disease data and statistics targets a specific disease, HIV/AIDS receives the most funding.[12] This increased in 2018 and 2022, likely due to the timing of disbursements to HIV rather than an increase in spending (Wexler, Kates and Oum, et al. 2023).

Figure 3 ODA disbursements (US $ million) for infectious disease data and statistics by disease between 2018 and 2022

Million USD

Figure data available here.

Source: ODW analysis based on PRESS 2024.

HIV and TB surveillance have been strongly impacted by reductions. USAID, the National Institutes of Health, CDC, and PEPFAR funding significantly contributed to TB and HIV research. PEPFAR targeted key populations such as men who have sex with men, sex workers, people who inject drugs, and children orphaned by AIDS. These populations that are vulnerable to socioeconomic stresses are more likely to contract HIV and will be disproportionately harmed by the reductions to PEPFAR’s budget. As a result of the freeze in funding, reports of stigmatization and discrimination are already increasing, especially in contexts in which homosexuality is highly stigmatized or criminalized. The reported rise in discrimination makes monitoring these key populations increasingly challenging (Global Black Gay Men Connect 2025, 19). Disruptions to HIV trend analysis will prevent health officials and workers from accurately directing responses and resources to these populations, leaving millions without life-saving care (Ekpunobi 2025).

South AfricaSignificant investment in HIV and TB research went to South Africa, which acted as a hub for HIV and TB research and development. Funding halts disproportionately affect pregnant women, infants, and youth, and vulnerable populations. According to one report by the Treatment Action Group, Doctors without Borders, and the South Africa Medical Research Council, “terminating awards to South African sites could affect up to 30 percent of participants enrolled in TB trials” and 50-90 percent for pediatric and pregnant populations, which in turn limits the ability of health practitioners to support these populations (Treatment Action Group, Médecins sans frontières, and SAMRC 2025). |

Breaks in time-series continuity erode cause-of-death data quality, weakening estimates of disease burden and slowing outbreak detection. The suspension of DATIM analytics reduces the capacity of the International Severe Acute Respiratory and emerging Infection Consortium (ISARIC) to trigger rapid research responses during new outbreaks, especially in hubs in LMICs (ISARIC 2023). Delays to MICS and DHS—primary sources of health data in many sub-Saharan African countries—also jeopardize disease-modeling initiatives that fund researchers based in Africa. Disruptions to national HMIS platforms undermine epidemic hotspot detection in major African research hubs.

5.3 Climate and Health

Climate and health programs focus on building the evidence base linking climate change to health outcomes and supporting interventions that reduce health harms from climate-related exposures. This work will be heavily impacted by interruptions to time-series continuity and the erosion of technical capacity. Global reductions in funding are expected to affect funding for climate and health and nutrition data because these areas were already operating with tight budgets from only a few donors. According to the PRESS analysis, the top two donors for climate and health data in 2018–2022 were the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN (FAO) ($13,409,829) and the UN’s Green Climate Fund (US $2,159,784), together accounting for 71 percent of all funding ($21,903,590). In 2025, the FAO’s funding from the United States was frozen, and the United States put pressure on the FAO to return to its core mandate and end its “distracting focus on climate” (Karas 2025). The Green Climate Fund’s funding from the United States was rescinded in 2025 (Mathiesen 2025). The reductions in funding for these two organizations are expected to significantly hamper climate and health data and statistics.

Potential impacts due to reductions in funding in this area include interruptions to time-series continuity, undermining time series studies needed to assess the health impacts of climate variability (WHO 2025c),[13] technical capacity losses affecting in-country partnerships used for community-level exposure assessments, and delays or degradation in CRVS and surveillance data impacting early-warning tools for climate-sensitive health risks.

Interruptions to ongoing time-series data collection for climate and health programs have already taken place. Rising temperatures and increased incidence and severity of climate disasters are worsening world hunger and famine conditions (World Food Program 2024). This makes services such as the Famine Early Warning System Network (FEWS NET) crucial to forecasting famine conditions. FEWS NET went offline for nearly six months following the cancellation of USAID funding (Mersie 2025), leaving millions of those experiencing environmental and humanitarian crises and those responding to the crises without critical data and information to inform action (Emanuel 2025). However, even with the return of FEWS NET services in June 2025, the impacts of time-series breaks are ongoing. FEWS NET typically forecasts six to nine months in advance, but its maps currently have no forecasting data and only provide data through May 2025 (FEWS NET 2025). FEWS NET is only one example of how the changes to funding affect climate and health data.

5.4 Discovery Research

Discovery research encompasses multilateral partnerships, basic science, data infrastructure, and long-term cohort studies to advance biomedical knowledge. Long-term cohort studies funded under discovery research often track population health over decades to understand biomedical and environmental influences. Many such research projects rely on high-quality longitudinal administrative and survey data (Cole, et al. 2020). For example, over 6,000 peer-reviewed research papers have been published based on DHS data alone (Khaki, et al. 2025). Interruptions to these administrative and survey data hinder health research globally. According to PRESS analysis, countries classified by the United Nations as least developed (LDCs) are most likely to be impacted by the research cuts, as nearly one-third (32 percent) of all discovery research ODA in 2018–2022 ($92,356,524 of $288,267,482) went to LDCs from multilateral organizations. Similarly, just under a third (32 percent) went to sub-Saharan African countries ($93,243,552 of $288,267,482).

Programs that include research with a gendered and inclusive health focus (such as data on persons with disabilities, ethnic minorities, and LGBTQ+ individuals) are more likely to be impacted by reductions in funding (UN Women 2025). As a result of several executive orders, sub-recipient organizations of U.S. foreign assistance were told to sign documents promising they would not provide services related to gender or equality, diversity, and inclusion if they were to be eligible for funding waivers (Global Black Gay Men Connect 2025). Additionally, under these orders, CDC personnel were told to remove all data and research that involved gender and sexuality, even when related to basic demographic data (Walters 2025, Heidt 2025). These actions set back medical knowledge, especially among LGBTQ+ individuals and women, by effectively erasing entire groups’ existence from the data.

One example of a research project halted by USAID funding reductions is the STOP Spillover research project that focused on preventing zoonotic viral diseases from becoming epidemics and pandemics. The suspension of this program and stop-work orders meant that all research was forced to stop, even if the data and samples were collected and waiting for analysis. For example, researchers in Liberia were left with freezers full of blood samples they were now unable to test (Cohen 2025). This exemplifies the waste of resources due to interruptions to basic research: even though the evidence had been collected, data could not be produced for use by researchers and policymakers.

Across the key areas discussed in this section, the estimates presented have drawn on ODA tracking and selected program reports. These sources align in the direction of change but leave gaps in understanding the full extent of philanthropic responses, government backfilling, and the durability of bridging measures. These uncertainties are developed further in the concluding section of this report.

Section 6: Immediate Responses to Changes in Financing

The abrupt contraction of funding and reductions to programs triggered a rapid effort by actors across the global health data ecosystem to manage the effect of the changes. These measures were often intended to be short-term initiatives to give countries and the global statistical system sufficient time to adjust while still ensuring that planned, essential health data activities, especially for emergencies and population trend monitoring, could continue.

6.1 Adaptation Measures by NSOs

In response to changes in the funding for global health data and statistics, NSOs have already begun to take immediate, adaptive measures. NSOs were most likely to strengthen partnerships with other national institutions (56 percent), mobilize financial support from national governments (53 percent), or increase cost-efficiency through innovation (53 percent) (ISWGHS 2025a). NSOs were least likely to intentionally delay censuses or surveys as an adaptive strategy (27 percent) (ISWGHS 2025a). However, delays also occurred due to circumstances beyond NSOs’ control; for example, about half of NSOs (53 percent) encountered or anticipated delays in implementation or release of results for their DHS since January 2025 (ISWGHS 2025a).

Morocco is an example of a country mobilizing financial support to strengthen resilience and national ownership. Most MICS surveys rely on UNICEF’s centrally managed CSWeb infrastructure. However, in 2025, with UNICEF’s support, Morocco’s Ministry of Health and Social Protection adopted a new approach in which they issued terms of reference for a domestically hosted CSWeb platform for MICS data, to be deployed and maintained on government servers (UNICEF, Ministère de Santé et de la Protection Sociale 2025). While this program was planned before the cuts, it serves as an example of how countries can build national ownership of survey infrastructure and reduce vulnerability to disruptions in donor-provided systems.

;6.2 Emergency Survey Stopgaps

The most immediate responses to the 2025 funding reductions came in the form of stopgap measures aimed at preventing the collapse of DHS surveys already in the field. Private philanthropies moved quickly to ensure the completion of these surveys. The DHS Program announced a US $39 million grant that would enable it to continue several surveys disrupted in mid-enumeration; subsequent reporting confirmed that funding came from the Gates Foundation and Bloomberg Philanthropies (Pawar, 2025; Gates Foundation, n.d.). National governments also made emergency reallocations. Nigeria diverted roughly US $200 million from other development priorities to sustain DHS field operations and shore up parallel disease control programs simultaneously affected by the suspension of U.S. aid (Shibayan 2025). These interventions allowed enumerators to finish data collection and ensured that partially completed surveys would not be abandoned, but they do not resolve long-term financing.

These stopgaps bought valuable time. They prevented the immediate collapse of population health data in several countries and allowed policymakers to continue drawing on at least some recent evidence. However, these are emergency fixes, and the fundamental question of how demographic and health data will be financed in the years ahead remains unresolved. Without stronger coordination among donors and multilateral organizations, these fixes will remain fragmented, leaving essential surveys exposed to recurring cycles of disruption.

6.3 Civil Society and Data Preservation

Alongside official and donor-led responses, civil society organizations, academic institutions, and advocacy groups mobilized to safeguard access to demographic and health data. These efforts were often modest in funding and scope, but they played a critical role in preventing data loss at a time when institutional mechanisms faltered.

Archiving initiatives were among the first responses. The Data Rescue Project began cataloguing DHS summary indicators, metadata, and geocoded files in open repositories, ensuring that researchers could continue to draw on at least partial series even if full survey rounds stalled (Khaki, et al. 2025). Similarly, academic consortia such as Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS) International worked to maintain continuity of microdata access by integrating DHS data into broader harmonized datasets, buffering researchers against the immediate impacts of funding reductions (Khaki, et al. 2025).

Advocacy groups also pressed for recognition of DHS data as a global public good. The Population Reference Bureau and allied NGOs highlighted the risks of data loss to gender equity, health financing, and accountability, calling on donors to commit to preserving historical DHS datasets and guaranteeing access (PRB 2025). These campaigns sought not only to protect existing data but also to raise the political visibility of the crisis to influence donor priorities.

By keeping data accessible, these preservation efforts bridged the gap between emergency fixes and longer-term alternatives. They maintained continuity for policymakers, researchers, and civil society actors dependent on DHS data, and they reinforced the principle that demographic and health information, should remain accessible, even in times of budgetary crisis. While these efforts bought time, longer-term strategies are needed. Section 7 examines how governments, donors, and multilaterals are beginning to shift toward more sustainable approaches.

Section 7: Longer-Term Responses to Changes in Financing

The changes in funding and immediate responses revealed not only the resilience of governments, donors, and civil society but also the fragility of a system dependent on a heavily concentrated funding base. Actors’ responses aimed to cover immediate needs for health data and statistics, and they also sought to build better, more sustainable health data systems. Longer-term responses include better integrating data and statistics into existing channels and frameworks, innovating by using different data sources, prioritizing existing funding, and developing a diversified model for coordination and standardization.

7.1 Mitigation Measures by NSOs

In addition to some of the immediate responses undertaken by NSOs, most responding NSOs (62 percent) have also started to plan for and put in place longer-term (5–10 years) coping measures that ensure the long-term sustainability of data collection (ISWGHS 2025a).The more common mitigation measures that NSOs reported using were integrating surveys into national budget planning processes (56 percent) and expanding the use of other data sources such as administrative, citizen, or other non-traditional sources (53 percent) (ISWGHS 2025a).

ThailandThailand has been hailed as an example of domestic HIV/AIDS response, especially in the wake of funding cuts. Thailand received PEPFAR funds but funded 91 percent of its HIV/AIDS response. This sustainable funding model comes in part from institutionalized HIV/AIDS services in Thailand’s universal health system. Furthermore, the Thai government partners with community-based organizations to fund HIV/AIDS services, largely to marginalized communities. Community interventions “are now responsible for identifying half of new HIV diagnoses in Thailand and supporting about 80 percent of people on [pre-exposure prophylaxis]” (Bajaj 2025). This intervention model can be applied to other infectious diseases, strengthening vertical disease surveillance. |

7.2 Donor and Multilateral Bridging Measures

Beyond immediate survey stopgaps, donors, multilateral organizations, and global health partnerships introduced measures to preserve service delivery and sustain core data functions. These actions were essential in keeping programs alive, but they often came at the cost of longer-term investments.

Some of the first commitments at the system level came from philanthropic institutions. Wellcome announced $5.6 million to support South Africa’s Medical Research Council after it lost a major U.S. grant, while Rockefeller partnered with Wellcome to launch a $11.5 million initiative to sustain climate and health data infrastructure (Khaki, et al. 2025). Multilateral organizations reprioritized resources: the WHO rolled out a rapid plan to sustain HIV, hepatitis, and sexually transmitted illness services and monitoring in LMICs (WHO 2025d), while UNAIDS mobilized governments, communities, and donors to assess the impacts of the U.S. funding pause and ensure continuity of HIV prevention, treatment, and commodity supply chains (UNAIDS 2025a).

Global health partnerships also redirected funds. The Global Fund initiated a sweeping reprioritization of its grants in response to the crisis. Lifesaving interventions such as antiretroviral therapy and insecticide-treated bed nets were preserved, but survey programs, training initiatives, and infrastructure upgrades were postponed or canceled (Global Fund 2025). Similarly, Gavi introduced a “Resilience Mechanism” to ensure continuity in immunization and monitoring programs, backed by over $9 billion in new pledges at its 2025 replenishment round (Rigby 2025). UNFPA is likewise committed to sustaining reproductive and sexual health services and monitoring by reallocating resources (Khaki, et al. 2025).

Not all bilateral donors responded by cutting back. According to IHME, both Australia and Japan modestly increased their DAH in 2025 by 2.6 percent (about $18 million) and 2.2 percent (about $30 million), respectively (Apaeagyei, Bariş and Dieleman 2025). These limited increases were far smaller than the large-scale withdrawals by major donors, but they highlight that some governments continued to expand support, even in a constrained funding environment. These actions demonstrate continued commitment, but without a forum to bring efforts together, their overall impact is limited and risks leaving critical systems unevenly supported.

National governments also began taking visible leadership in convening financing coalitions. Côte d’Ivoire organized a high-level donor roundtable in 2025 to mobilize CFA 43 billion (about US $70 million) to finance its DHS round (Yeo 2025). Burkina Faso’s NSO, Institut National de la Statistique et de la Démographie, held public meetings to engage partners in funding its upcoming MICS cycle, explicitly highlighting the need to broaden its support base beyond the United States (INSD 2025). These examples show how governments are stepping into coordination roles and are actively mobilizing and negotiating to sustain survey operations.

7.3 Ongoing and Expanded Coordination Efforts

Recognizing that temporary fixes could not sustain a system built on external support, governments and international agencies began designing more durable models. These initiatives sought to assess the consequences of the interruptions to the DHS Program and to chart pathways toward nationally owned, financially sustainable alternatives.

Several donor and policy debates have focused on ensuring a collective understanding of the current challenges to data collection and planning for future efforts. These early discussions point to the importance of a credible convener who can turn dialogue into actionable coordination, ensuring that financing and technical standards are addressed together. At the geopolitical level, the Munich Security Conference warned that the gap in demographic and health data was “too big to fill” with piecemeal measures (Kump 2025). A Population Reference Bureau meeting in early 2025 called for coalition-building among donors, NSOs, and research institutions to explore models beyond the DHS framework (PRB 2025). Together, these discussions represent the first coordinated attempts to move beyond temporary financing solutions toward a more diversified data architecture rooted in national ownership and sustainable financing.

The most significant step was the establishment of a taskforce under the UN Statistical Commission’s Inter-Secretariat Working Group on Household Surveys. The taskforce was mandated to ensure access to existing DHS data as a public good, document the impacts of DHS Program interruptions, develop long-term sustainable survey solutions, and pilot nationally owned health survey programs (ISWGHS 2025b, ISWGHS 2025c).

Section 8: Conclusions and Recommendations

Reductions and changes in funding have exacerbated weaknesses in the global health data system, including its dependence on a small group of donors, concentrated technical capacity, and weak enabling environments. Low-income countries are particularly impacted by the reductions as they are more likely to have tight budgets, have lower capacity, and, as a result, be more reliant on donors.

Reductions in funding in 2025 have been particularly challenging due to their size and abruptness. As a direct result of reductions and changes in funding, time-series continuity was interrupted, and technical capacity and operational reliability were reduced, leading to impaired disease modeling and inhibiting basic research. The reductions in funding will impact climate, health, and mental health more because these areas do not have as much of a buffer in their budgets. Without data and a way to track and model trends in health, practitioners are less able to make timely, evidence-based decisions.

In response, practitioners have begun to take some adaptive measures. Some NSOs were able to quickly mobilize domestic and novel resources, and global actors were able to provide some temporary funding so there can be a transition period before funding is further reduced. The global statistical community has also begun to look at ways to create a more resilient global health data system that approaches health in a holistic manner and is more focused on country needs. Global conversations indicate that the global statistical community should also continue to coordinate and provide standards for global health data collection and indicators. These steps are critical but remain insufficient on their own. To avoid repeated cycles of fragmentation, stronger convening is needed to align donors, multilaterals, governments, and civil society around coordinated financing and common standards.

Several uncertainties remain: the duration of donor withdrawals, the extent of philanthropic contributions, and the degree to which governments can step in are all still unclear. These gaps heighten the risk of uneven support and complicate plans for sustained data systems. Against this backdrop, the recommendations that follow emphasize actions that remain valuable across a range of possible futures and can be undertaken by a variety of actors.

8.1 Next Steps

- Put countries in the lead with clear national ownership and governance and secure multi-year financing that spreads risk.

Sustainable solutions start when governments set the agenda and partners align behind them. National ownership reduces fragility, improves relevance, and ties methods and release schedules to domestic priorities.

Governments (national statistical offices, health ministries, and civil registration authorities) should set priorities and methods through costed national strategies and sector plans, and partners align to these plans rather than donor-specific workplans. Domestic budgets should include dedicated lines for periodic demographic and health surveys, civil registration and vital statistics (CRVS), and routine health information systems (e.g., DHIS2) operations and maintenance, under clear mandates that clarify roles for data stewardship, data protection, and public release.

Financing should be planned over several years, coordinated against a single country plan, and delivered through country systems rather than in parallel. Pooling and flexible contributions help avoid stop-start cycles that break time series. Donor contributions should be routed through domestic budget lines, co-financed basket funds, or national procurement and audit processes. Country-led coordination should map partner commitments to the single plan and track funding and delivery milestones, surfacing unfunded priorities early so gaps are addressed before core series or platforms stall.

- Build and retain core statistical capacity with structured regional support.

Resilient national data systems are built on institutional capacity, not short-term fixes and projects. Countries need stable, well-trained teams for survey design and operations, CRVS and HMIS administration, data processing and quality assurance, privacy protection, and analysis and communication.

Governments should resource permanent roles and career paths for survey design, field management, data processing, CRVS operations, HMIS/ administration, data protection, and analysis and communication within recurrent budgets. Development partners should back multi-year training and mentoring rather than short consultancies, including partnerships between national agencies and universities. When countries face temporary gaps, regional statistical organizations can organize short, time-bound technical assistance, coordinated as relevant with WHO/UNICEF regional offices and the DHIS2/HISP network, so help arrives without displacing national staff. All support should leave behind documented methods, codebooks, and process checklists so that skills are institutionalized rather than held by individual contractors.

- Protect continuity and comparability through shared standards and open access.

Better data standards and openness turn separate datasets into a coherent evidence base for health policy. They safeguard trend comparability and multiply the value of each data investment.

Standards and modules to ensure microdata availability and ease of access should be developed through global consultation—endorsed by the UN Statistical Commission and supported by expert inter-agency mechanisms such as ISWGHS and its Task Force—and then adopted and published by countries (NSOs, health ministries, and civil registries) so results remain comparable across years and countries. Fieldwork calendars should be coordinated to avoid long gaps and unnecessary trend breaks, with release calendars and metadata published in advance. Donors and multilaterals should link technical support to adherence with agreed standards and to the timely publication of anonymized microdata and documentation, following open data and FAIR principles (findable, accessible, interoperable, reusable). Regional statistical organizations can facilitate peer review, while guidance from the ISWGHS Task Force and IAEG-SDGs provides toolkits and templates for questionnaires, codebooks, APIs, and metadata. National data portals and microdata libraries should serve as the authoritative archives, with privacy safeguarded through documented anonymization and access procedures.

- Use public monitoring to align financing, production, and access.

Regular and transparent feedback identifies problems early and keeps financing, production, and use of data aligned with national plans.

The use of capacity measures, such as indicator 17.18.1 (measure of statistical capacity to produce data for the Sustainable Development Goals), could support results monitoring. Also, the use of existing platforms—such as the Clearinghouse for Financing Development Data —can bring together country plans and funder commitments in one place. The Clearinghouse serves both as a platform to improve the transparency and coordination of financing for data, and as a community advocating for smarter, evidence-based investments. The Clearinghouse also features research to strengthen how we track and analyze data flows, helps identify gaps, aligns funding with priorities, and supports more effective resource allocation.

Civil- society and other partners can turn inputs from platforms and databases into advocacy products that flag gaps, delays, and adherence to standards, and promote good practices. Regional and global forums (e.g., ISWGHS, IAEG-SDGs) can in turn use open data and advocacy products to host periodic sessions and feed decisions back into budgets and workplans.

Endnotes

[1] The NSO rapid assessment survey data cited here are pre-release and considered confidential until publication by the UN Task Force later in 2025. Findings are presented for analytical purposes only and may be revised.

[2] The unit costs and costs for improvements of administrative systems and censuses were the result of several rounds of consultation conducted with survey statisticians for the Data for Development report (SDSN 2015). They have been converted to 2023 price levels according to USD inflation.

[3] See also the America First Global Health Strategy (U.S. Department of State 2025), which emphasized cost-sharing and bilateral agreements.

[4] The survey was coordinated by the UN Task Force on Sustainable Demographic and Health Statistics (ISWGHS, UN Women, IAEG-SDGs, World Bank) and sent to 130 NSOs in low- and middle-income countries. Sixty-six offices responded, a 51 percent response rate.

[5] 45 NSOs reported budget reductions. Percentages referring to “impacted NSOs” use these 45 NSOs as the denominator.

[6] According to the DHS Program website, 30 countries who responded to the NSO survey have conducted a DHS survey since 2015. These countries were used as the denominator for DHS Program related questions in the NSO survey.

[7] Khaki et al. estimates four surveys were completed but unpublished, seven were in mid-fieldwork, and eleven in early preparation.

[8] Although the U.S. Senate and House approved legislation in July 2025 exempting PEPFAR from the rescissions package, thereby safeguarding its overall funding (Rescissions Act of 2025, Public Law 119-28), uncertainty remains about how quickly services will recover and whether future funding will remain secure.

[9] PRESS is a filtered version of OECD’s Creditor Reporting System dataset that contains entries that are related to statistical capacity building. The dataset can be downloaded here. See Appendix B for more information.

[10] The PRESS dataset does not have an official code for discovery research. Instead, PRESS purpose codes that included research, education, training, and personnel development for health data and statistics were grouped as discovery research.

[11] Figures based on an ODW analysis of PARIS21 Partner Report on Support to Statistics (PRESS) 2024 data.

[12] Some programs targeted more than one disease. To capture the relative attention given to each disease, these programs were counted under each relevant disease area. As a result, the infectious disease disbursement totals in this figure are not identical to those shown in Figure 2.

[13] For example, the State Department decided in 2024 to halt sharing air quality data from US embassies which will harm projects examining pollution’s impacts on health.

References

ACAPS. 2025. Ethiopia: Implications of the US Aid Freeze & Terminations. March 13. Accessed September 1, 2025. https://www.acaps.org/fileadmin/Data_Product/Main_media/20250313_ACAPS_Implications_of_the_US_aid_freeze___terminations_for_Ethiopia.pdf.

Anand, Sai Priya, Clarence C. Tam, Sharon Calvin, Dima Ayache, Lisa Slywchuk, and Irene Lambraki. 2024. “Estimating public health risks of infectious disease events: A Canadian Approach to rapid risk assessment.” Canada Communicable Disease Report 50 (9): 282-293. doi:https://doi.org/10.14745/ccdr.v50i09a01.

Apaeagyei, Angela, Enis Bariş, and Joseph Dieleman. 2025. Financing Global Health 2025: Cuts in Aid and Future Outlook. July 15. Accessed September 1, 2025. https://www.healthdata.org/research-analysis/library/financing-global-health-2025-cuts-aid-and-future-outlook.

Apaeagyi, Angela E., Bisignano Catherine, Hans Elliott, Simon I. Hay, and Brendan Lidral-Porter. 2025. “Tracking development assistance for health, 1990–2030: historical trends, recent cuts, and outlook.” The Lancet 406 (10501): 337-348. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(25)01240-1.

Bajaj, Simar. 2025. “The U.S. slashed HIV/AIDS funding. Here is how countries that relied on it might adapt.” Stat, June 3. https://www.statnews.com/2025/06/03/hiv-aids-pepfar-cuts-usaid-how-countries-like-thailand-adapt-global-funding-crisis/.

Bartlett, Kate. 2025. “UNAIDS report warns that HIV progress is at risk as U.S. funding cuts take hold.” NPR, July 10. Accessed September 22, 2025. https://www.npr.org/2025/07/10/nx-s1-5463547/unaids-south-africa-trump-hiv-aids.

Cohen, Jon. 2025. “Trump cuts damage global efforts to track disease, prevent outbreaks.” Science, March 25. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adx7213.

Cole, Shawn, Iqbal Dhaliwal, Anja Sautmann, and Lars Vilhuber. 2020. Handbook on Using Administrative Data for Research and Evidence-Based Policy. September 25. Accessed September 4, 2025. https://admindatahandbook.mit.edu/book/v1.0-rc2/intro.html.

Community Commons. n.d. Administrative data. Accessed September 8, 2025. https://www.communitycommons.org/entities/a0c5a93e-aef1-4987-bdad-3331c39f8936.

Cullinan, Kerry. 2025. “Tedros urges countries to support ‘modest budget’ – and help close $1.7 billion gap.” Health Policy Watch, May 19. https://healthpolicy-watch.news/tedros-urges-countries-to-support-modest-budget-which-still-has-1-7m-gap/.

Dattani, Saloni. 2025. The Demographic and Health Survey Brought Crucial Data for More Than 90 Countries – Without Them, We Risk Darkness. July 21. Accessed September 1, 2025. https://ourworldindata.org/demographic-health-surveys-risk.

DHS Program. n.d. DHS Program. Accessed September 8, 2025. https://dhsprogram.com/.

—. 2015. Establishment of a Collaborative Group among the DHS, MICS and LSMS. May 13. Accessed September 1, 2025. https://dhsprogram.com/Who-We-Are/News-Room/Establishment-of-a-Collaborative-Group-among-the-DHS-MICS-and-LSMS.cfm.

Ekpunobi, Nzube. 2025. Implications of Potential Pepfar Funding Cuts on Nigeria’s HIV/AIDS Response: A Critical Review. February 13. Accessed September 1, 2025. doi:https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202502.0837.v1.

Emanuel, Gabrielle. 2025. “U.S. famine warning system comes back, but questions loom.” NPR, August 11. https://www.npr.org/2025/08/11/nx-s1-5475193/u-s-famine-warning-system-comes-back-but-questions-loom.

Executive Office of the President. 2025. “Reevaluating and Realigning United States Foreign Aid.” Federal Register 90 (19): 8619. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2025/01/30/2025-02091/reevaluating-and-realigning-united-states-foreign-aid.

FEWS NET. 2025. Home page. Accessed September 4, 2025. https://fews.net/.

Fisher, Stacy, Carol Bennett, Dierdre Hennessy, Tony Robertson, and Alastair Leyland. 2020. “International population-based health surveys linked to outcome data: A new resource for public health and epidemiology.” Health Reports 31 (7): 12-23. https://www.doi.org/10.25318/82-003-x202000700002-eng.

Flaxman, Abraham D., Sylvia Lutze, and Alison Bowman. 2025. Visualizing Nutrition Deficits After USAID’s Overhaul. May 15. Accessed September 1, 2025. https://www.thinkglobalhealth.org/article/visualizing-nutrition-deficits-after-usaids-overhaul.

Fletcher, Elaine Ruth. 2025. “WHO budget cuts may slash 30% of mid-level staff, spare most senior roles.” Health Policy Watch, May 16. https://healthpolicy-watch.news/who-projects-30-reduction-in-mid-level-professionals-for-26-27-few-high-level-staff-to-go/.

Gates Foundation. n.d. Committed grants. Accessed October 1, 2025. https://www.gatesfoundation.org/about/committed-grants/2025/07/inv-090390.