View the PDF print version of this publication at Open Data Charter.

Key Messages

- Existing guidelines around the use of data in VNRs does not explicitly call for open data in SDG reporting but uses language that could facilitate open data practices.

- How available data are in voluntary national reviews mirrors how available they are in global databases, such as the SDG Global Database.

- The guidance that does exist on the use of data in VNRs is followed piece-meal by countries: Around half of all countries use data annexes but few if any are transparent around the source of data.

- Based on the sample of 11 countries, those that have more open data policies also publish more data heavy or data forward VNRs.

- Countries should be encouraged to publish more of their data in VNRs with citations and linked to data sources in order to improve transparency and spur greater coordination between data providers of the national statistical system.

Introduction

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are a call for action by all countries – regardless of income level – to promote prosperity while protecting the planet. The SDGs recognize that ending poverty must go hand-in-hand with promoting economic growth, addressing social needs including education, health, and social protection, while tackling climate change. These goals also provide a critical framework for ongoing COVID-19 recovery. However, the SDGs are off-track in implementation and monitoring: even with the laudable advancements of the past eight years, clear concepts and good coverage exist for only 66 percent of SDG indicators. Additionally, goals like SDG 5 on gender equality and SDG 13 on climate change have internationally comparable data for less than half of 193 countries or areas since 2015 (UNSD, 2023). However, past progress on health data (SDG 3) offers hope.[1]

There are two main mechanisms to track progress:

- Countries submit data to custodian agencies that compile data as part of the SDG framework, which is then published by the UN Statistics Division (UNSD) on the SDG Global Database and from which UNSD then develops reports on the implementation of the SDGs, such as through the annual SDG reports.

- Countries prepare a review of the implementation of the SDGs in their country by submitting a Voluntary National Review (VNR). Through these VNRs, governments share their experiences, including successes, challenges and lessons learned in implementing the 2030 Agenda. They also seek to strengthen policies and mobilize support and partnerships for the Sustainable Development Goals.

When this happens, critical information on progress towards key development domains is locked away, hindering both an understanding of a country’s current progress towards the SDGs and the ability to make necessary changes for improvements. And when the data that governments compile for reporting mechanisms like the VNRs are not open[3] or accessible for different stakeholders (Civil Society Organizations, Academia, etc.), or even for government agencies themselves, it significantly limits the value of the reported data.

A lack of openness also goes against the fundamental human right of access to public information. Data on the SDGs also fall under this right. Openness can also help public institutions by lowering the costs and time needed to generate reports in accordance with international obligations and to make evidence-informed public policy decisions. For citizens, openness improves accountability and monitoring, and allows citizens to add value to data through reuse. At the international level, ‘open by default’ is now endorsed as a guiding principle for official statistics and open data are a regular item for discussion at the United Nations Statistical Commission. Yet implementation of this principle is often uneven: Only 27 national governments have signed up to the Open Data Charter[4] (Open Data Charter, 2024) and while global openness scores on the Open Data Inventory (ODIN) have improved from 38 to 57 out of 100 (Open Data Watch, 2023), this still leaves too few countries with a practical implementation of government open data policies. In addition, it is not fully understood how countries apply the open data principle throughout all of their operations, particularly with regard to SDG reporting.

Objective

Open Data Charter and Open Data Watch set out to answer questions around how accessible the data are in VNRs and whether these SDG reporting practices correspond to countries’ own open data landscapes. Guidance on integrating data into VNRs exists but it falls short of advocating for open data (see next section). By investigating the questions above, this research seeks to formulate recommendations for offices responsible for VNR formulation. These recommendations will:

- Improve transparency and access to information for citizens and public officials on topics such as national progress towards the SDGs and encourage the use of these data by citizens;

- Reduce the costs and time required to generate both VNR and SDG reporting;

Future work will seek to understand how the different country reporting organizations and national statistical organizations are internally organized and coordinate SDG reporting in order to refine these recommendations.

Methodology

Open Data Charter and Open Data Watch have conducted a pilot assessment of the availability and openness of data regarding three SDGs in VNRs of 11 countries across a range of incomes and geographies.[5] The pilot assessment focuses on SDG 5 (Gender equality), SDG 13 (Climate change), and SDG 3 (Health) due to the substantial global data gaps in gender equality and climate change and to use health data as a comparison case as a successful case study of improving data systems over time. By comparing the availability and openness of data regarding these three goals in country VNRs, this brief reveals how countries are using and disseminating data on these crucial development topics. This report describes the existing resources available by the UN to support countries in the development of their VNRs and examines how well the countries deliver on the provided recommendations for how to report.

In addition, for each country, the existing governance structure for government open data is examined to provide the context within which the selected VNRs are produced. This report highlights discrepancies between these two areas of investigation to show where VNR practices and policy coherence can be improved.

The Voluntary National Reviews and Open Data

What are the guidelines for VNRs and data?

UNSD provides technical assistance to countries interested in preparing VNRs and publishes guidance manuals that are periodically updated. The “Handbook for the Preparation of Voluntary National Reviews – 2024 Edition” (“Handbook”) is the most recent resource available and guides countries in the preparation of VNRs together with the Secretary General’s guidelines (also included in the Handbook). Further guidance is available from UNSD in the form of the Repository of Good Practices in VNR Reporting (“Repository”) and most relevant for the integration of data into VNRs, the Practical Guide for Evidence Based Voluntary National Reviews (“Guide”). Each resource varies in the extent to which it refers to open data or offers specific guidance on how to use data in the VNR.

HandbookOpen data is not described specifically in the publication. However, there is language to suggest that data used in VNRs should be broadly open: Guiding principle G stresses that “[VNRs] will be rigorous and based on evidence, informed by country-led evaluations and data which is high-quality, accessible, timely, reliable and disaggregated…” Authors are also encouraged to ask themselves “What efforts are being made to monitor the indicators and ensure transparency and accountability?” as part of preparing the VNR. Finally, the data section of the Handbook recommends that “Contacts with the national statistical office and other providers of data should be part of the [VNR] planning process. If a statistical annex is included in the review, more extensive statistics on progress can be included there.”

While these principles and recommendations emphasize the importance of open processes to develop VNRs, accessible data, and some specific aspects of reporting data, they do not mandate or explicitly refer to open data.

RepositoryThe Repository goes further in its advocacy for open data but does not mandate it. The Repository highlights the importance of data-informed VNRs in Chapter 3: “Availability is only one part of the data challenge. The quality of data is the second, and strengthening national statistical systems is the third. None of them will be complete if countries fail to communicate data in an open and understandable way.” The chapter emphasizes the importance of the engagement of national statistical offices in the preparation of VNRs, monitoring and data visualization, using data annexes, and using non-official data sources. However, this does not entail open data recommendations. Guide

The document includes detailed recommendations for how to use data in the VNR, including recommendations consistent with open data principles but does not use open data as an outright recommendation. The document does list the Open Data Charter as an example of guiding principles and proposes a data roadmap for VNRs, which includes establishing a VNR data team and recognizing policies and legal standards that inform SDG monitoring. Furthermore, Section 4 of the data roadmap emphasizes the need for good citations and sourcing throughout the VNR, consistent with principles of clear metadata under open data standards.

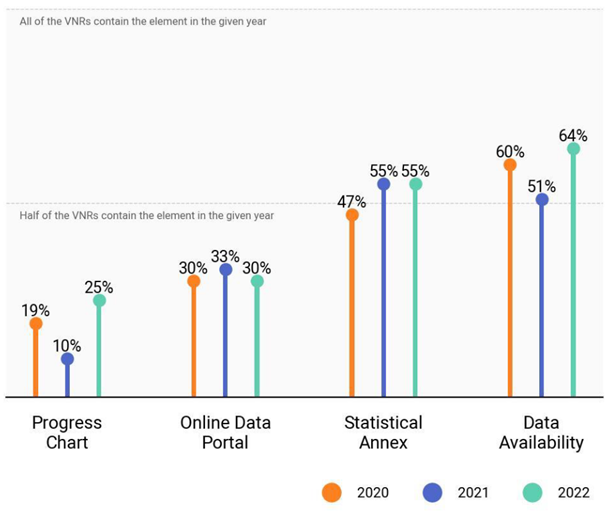

The Guide also includes the following graphic, which contains an assessment of the availability of ‘data elements’ in VNRs.

Figure 1: Proportion of countries incorporating data elements in VNRs (2020-2022)

Note: Data availability refers to the provision of the proportion of global or national SDG indicators with available data. Progress chart refers to the visualization of a trend analysis on the SDG progress. Online data portal refers to an open data source through which national SDG data are disseminated. Statistical annex refers to the documentation of SDG data.

The aforementioned sections of the handbook, repository, and guide all encourage countries preparing VNRs to use the country’s official statistics and to ensure they are used in the publication, including with proper citations. The next sections test this aspiration for several countries.

What is the coverage of this study?

The ODW and ODC research team selected eleven countries to assess the Voluntary National Reviews (VNRs) they submitted from 2020 onwards. The countries were selected based on regional and income level diversity. Of these eleven countries, one is a low income country (Ethiopia); four are lower middle income countries (Bangladesh, Ghana, Mongolia and Samoa); three are upper middle income countries (Colombia, Dominican Republic and Fiji), and three are high income countries (Canada, Germany and Spain) according to the World Bank FY2024 income groups.

How are open data and open government recognized?

Before assessing the depths to which data are included in VNRs, the ODW and ODC research team comprehensively assessed if open data or open government are mentioned in each VNR. This simple exercise provides a starting point for the deeper analysis by showing how countries talk about data overall in the context of SDG monitoring.

Across the 11 VNRs, six have mentions of open data. For example, in the case of Ghana, the VNR recognizes how Ghana Statistical Service “aims to make data more open for reuse, ensure better communication, and visibility of data, ensure data connects to decision-making and meets user need and ensure that data is interoperable and harmonized” (p. 135). Three countries mention open government, and Spain’s VNR mentions both open government and open data. In the case of Germany, the VNR recognizes that Germany is a member of the Open Government Partnership. The extent to which these standards or international commitments are referred to is interesting as a signal of what countries think is relevant to the task of SDG reporting. However, as the subsequent analysis will show, this does not necessarily translate into best practices in using data in their VNR.

How are data included in VNRs?

The ODW and ODC research team also looked at how data are included in VNRs, particularly if there are accompanying data tables or annexes to show any progress or monitoring of SDG indicators. For the purpose of this research, only SDG 3, 5, and 13 were assessed.

The team found that all VNRs have some inclusion of data, but an overwhelming majority of VNRs use data to make a narrative point. For example, Mongolia’s VNR provides data as context within their text: “Nationwide, 99.2 per cent of all births were attended by skilled health personnel in 2021, but 80 cases of unattended births were recorded. This is an increase of 14 cases, or 17.5 per cent, from the previous year” (p. 41). While all VNRs use some development data in text, six VNRs out of 11 also have a detailed annex for SDG data, in line with UNSD’s findings in their Guide (55% across 2021 and 2022).[6] And finally, two of the three high income countries (Canada and Germany) presented their VNRs from their perspective as a bilateral donor involved in efforts to achieve the SDGs in other countries Unfortunately, adopting this perspective means that very few data are available to highlight the progress of these countries themselves. Table 1 provides a summary of the 11 VNRs.

Table 1: Summary of VNRs by country

| Ghana | References of data in the VNR is primarily in a narrative style. 19 indicators across SDGs 3, 5 and 13 have some data references in existing sentences or graphics. There is not an annex page. |

| Mongolia | References of data in the VNR are in a narrative form with a supplementary annex. The supplementary annex has 29 indicators across SDGs 3, 5, 13. |

| Bangladesh | References of data are in a narrative form with a supplementary annex. The supplementary annex has 34 indicators across SDGs 3, 5 and 13. |

| Ethiopia | References of data are in a narrative form with a supplementary annex. The supplementary annex has about 31 indicators across SDGs 3, 5 and 13. |

| Fiji | References of data throughout the report in a narrative form with a supplementary annex. The supplementary annex has about 23 indicators across SDGs 3, 5 and 13. |

| Samoa | References of data in the VNR is primarily in a narrative style. That being said, about 21 indicators across SDGs 3, 5 and 13 have some data references in existing sentences. There is not an annex page. |

| Germany | This VNR is from the perspective of international cooperation, from a bilateral perspective. Therefore, about 6 indicators across SDGs 5 and 13 have some data references pertaining to Germany. No reporting of SDG 3. |

| Canada | This VNR is from the perspective of international cooperation, from a bilateral perspective. Thus, about 11 indicators across SDGs 3, 5, and 13 have some data references pertaining to Canada. |

| Spain | This VNR includes a data annex in a separate PDF. Thus, there are about 33 indicators across SDGs 3, 5, and 13 in the separate annex. |

| Dominican Rep. | This VNR includes graphics and data mentioned in a narrative style. There are 15 indicators across SDGs 3 and 13, and there is no reporting of SDG 5. There is not a separate annex. |

| Colombia | This VNR includes references of data throughout the report in a narrative form with a supplementary annex. The supplementary annex has about 34 indicators across SDGs 3, 5 and 13. |

What is the availability and accessibility of the data in VNRs?

Data related to SDGs 3, 5, and 13 were found in all VNRs examined by this study, however, they were not available evenly across countries due to countries’ different use of VNRs as a reporting tool.[7] Unless data were included in statistical annexes with clear links and citations, available data from VNRs were not easily found outside the document, which impedes accountability and does not suggest a high degree of interoperability and coordination between teams that prepare the VNR and organizations that administer the national statistical system, such as National Statistical Offices.

AvailabilityIn total, there are 392 data points across the 11 countries for SDGs 3, 5, and 13, which include any use of data, including repeated indicators or statistics. SDG 3 has 243 data points, SDG 5 has 86 data points, and SDG 13 has 63 data points. There is no ideal number of datapoints to include for each of the SDGs covered by this analysis, however, the availability of data for SDG 3 relative to the other two SDGs shows what can be done with sustained efforts and partnerships.

Countries range from 78 data points (Bangladesh) to 6 data points (Germany), with an average of 35.6 data points. Though only representing a small sample of countries, the high income countries included in this pilot study stand out for their low number of datapoints, 17 on average, compared to 37 for low income, 50 for lower middle income, and 35 for upper middle-income countries.

When just counting any mention of indicators across all countries, tuberculosis incidence (3.3.2) is reported by 10 out of 11 countries, with a long tail of indicators. Five more indicators, 3.1.1 on maternal mortality ratios, 3.1.2 on births attended by skilled healthcare professionals, 3.2.2 on neonatal mortality rate, 13.2.1 on national adaptation plan adoption, and 13.2.2 on greenhouse gas emissions, are all mentioned by 9 out of 11 countries.

In the number of data points and distribution of mentions across indicators, the data availability patterns of SDGs 3, 5, and 13 in the SDG Global Database are replicated in their use in even this limited sample of VNRs. This indicates that data are generally less available on these important areas of development than in others, or that data might be available in some parts of the system but not shared efficiently within the NSS for VNR preparation and for global reporting. Making the existing data more accessible can start to create the demand for more data, which enables a more virtuous cycle of data production.

AccessibilityAround sixty-three percent of all data points (246 out of 392) were cited in some way in the VNR text or statistical annex. However, only 11 data points out of the 246 with citations were linked to a source directly. A data source could eventually be found for just under forty percent of cited data points, but only after searching for them through google searches, presenting a hurdle to use and access.

The available Handbook encourages countries to provide timely and disaggregated data, as these data are used to monitor progress towards the SDGs. Best practices are shown in countries like Spain, where more detailed data are published in a separate annex, thus making data more available.

The fact that less than two-thirds of data points were cited and direct links were available for less than five per cent is concerning given the emphasis of the handbook, repository of best practices, and guide on accountability and transparency. Data from VNRs stands a much higher chance of being used if data are available to be checked and reused, rather than locked in tables that are not human or machine-readable.

Country policies on Open Data, Access to Information and Statistics

The VNR analysis mirrors the availability of data for SDGs 3, 5, and 13 in the global SDG database and finds that countries generally do not adequately cite and link the data they publish in their VNRs. This section connects these findings within specific documents to the open data policies and legal frameworks that these countries operate under to test for policy coherence. This examination reveals varying degrees of commitment and alignment with international standards and similar variance with their SDG reporting practices.

Do international commitments align with SDG reporting practices?

At the international level, there are several organizations and platforms that recognize, value, and promote the Right of Access to Information and Open Data.

The Open Government Partnership (OGP) promotes collaborative work between government and civil society to generate public policy commitments.[8] The Open Data Charter (ODC) is a collaboration between over 170 governments and organizations working to open up data based on a shared set of principles. ODC proposes practical tools for the collection, opening and reuse of data in specific thematic areas through the Open Up Guides. Regarding the SDGs that form the focus of this study, ODC has published the Open Up Guide to Advance Climate Action and the Open Up Guide for the Care Sector.

The adoption of the ODC and participation in the OGP varies among the countries under review, reflecting distinct approaches to fostering open data practices and government transparency.

Table 2: Countries and international commitments

| Country | OGP membership | ODC adoption |

| Colombia | Yes | Yes |

| Dominican Republic | Yes | Yes |

| Spain | Yes | No |

| Germany | Yes | Yes |

| Mongolia | Yes | No |

| Bangladesh | No | No |

| Canada | Yes | Yes |

| Samoa | No | No |

| Fiji | No | No |

| Ethiopia | No | No |

| Ghana | Yes | No |

Countries vary in how closely such commitments track with their VNR practices: Canada is a member of both OGP and ODC and has a special commitment on climate change, yet its overall availability of data points in its VNR is low. In fact is it only on Goal 13 (climate action) where Canada overperforms. The correlation between these commitments and SDG reporting is therefore in doubt, particularly as countries like Bangladesh, which reports the most data for each of the goals in its VNR, is a signatory to neither. This finding should act as an incentive for countries to align their global openness commitments with SDG reporting.

Do access to information legal frameworks track SDG reporting practices?

Access to public information is internationally understood as a fundamental human right. Particularly in this case, understanding the normative robustness of Access to Information, can be useful to think about the possible connection between the level of access to information and the achievement of the SDGs.

All the studied countries, except Samoa have established Access to Information (ATI) regulations, demonstrating a global commitment to fostering transparency.

Active transparency obligations[9] were found in the laws of seven countries, which demonstrates a proactive stance on publishing information; however, integrating these measures with SDG reporting practice remains a challenge based on the findings of this research. Linking active transparency measures to specific SDGs constitutes an opportunity for greater alignment between transparency practices and sustainable development objectives.

Global Right to Information Rating (RTI)The Global Right to Information Rating (RTI), seeks to establish parameters to analyze the robustness of the regulatory text on Access to Public Information, based on 7 dimensions: Right of access, scope, application procedures, exceptions and limits, appeals, sanctions and protections and promotional measures. According to the Index, Access to Public Information laws are present in 140 countries. The scale ranges from 1 (worst) to 150 (best).

Table 3: Global Right to Information Rating (RTI)

| Country | RTI Score |

| Colombia | 102 |

| Dominican Republic | 58 |

| Spain | 73 |

| Germany | 54 |

| Mongolia | 87 |

| Bangladesh | 109 |

| Canada | 93 |

| Samoa | No |

| Fiji | 64 |

| Ethiopia | 110 |

| Ghana | 97 |

Countries that have achieved higher scores also mention or include data in their VNRs. Colombia uses good practices when reporting progress, including data in the text of the report and in the annex, mentioning indicators on every SDG studied. Both Ethiopia and Bangladesh include data throughout the text of the report and in the annex. The annex has a detailed table of data.

On the other hand, Samoa does not have a score because it does not have access to information regulation and the references to data in the VNR are primarily in a narrative form, which makes it difficult to access the source and work with the information.

Germany’s score suggests areas for improvement in its right to information regime and its VNR, although written from the perspective of international cooperation, validates this finding.

Open data policies and the SDGs

Policies and portalsAn open data strategy (which can be implemented in different ways) is indispensable to improve internal processes, work on publication plans, promote interoperability and comparability, and ensure accessibility and regular updating. Information reported in open formats generates positive synergies within the government, and a greater impact on the society that reuses it (civil society organizations, universities, journalists).

The analysis of open data policies reveals a varied landscape in terms of legal frameworks and strategic approaches among the countries under review.[10] However, countries’ domestic open data commitments do seem to match their VNR practices.

Notably, countries such as Samoa, Fiji, and Ethiopia, currently lack dedicated open data policies or regulations. In these countries we can observe that the references of data in the VNR is primarily in a narrative form, which makes it difficult to access the source and work with the information. On the other hand, countries like Colombia have strong legal policies and an open data portal, which may have helped when preparing its VNR with many references to data and an exhaustive data annex.

Data rankingsIn addition to open data commitments and policies, as well as right to information laws, the performance of countries on international statistical capacity assessments like the Global Data Barometer are informative for investigating the coherence between domestic open data practice and country SDG reporting practices. Global Data Barometer

The Global Data Barometer (GDB) is a study that “evaluates countries around the world through a set of comparative metrics focused on data for the public good.” It has general modules (governance, capabilities), and thematic modules (climate change, healthcare, public procurement, etc.). Each of the modules measures various indicators. We will focus on a few of particular interest to our research below. Both the overall data openness of each country and the openness of specific topics deserves consideration.

Table 4: Global Data Barometer scores (0-100)

| Country | GDB general score | GDB climate score | GDB health score |

| Colombia | 52 | 45 | 57 |

| Dominican Republic | 35 | 15 | 54 |

| Spain | 56 | 61 | 54 |

| Germany | 58 | 55 | 83 |

| Mongolia | 33 | 36 | 42 |

| Bangladesh | 24 | 0 | 56 |

| Canada | 61 | 78 | 50 |

| Samoa | No | No | No |

| Fiji | No | No | No |

| Ethiopia | No | No | No |

| Ghana | 28 | 32 | 17 |

In the general data category, Canada emerges as a leader with a score of 61, indicating a robust framework for overall data governance. Spain and Germany also show strong performances with scores of 56 and 58, respectively. These scores suggest a commitment to comprehensive data policies. As mentioned before, these countries align their policies more closely with their reporting practices. Spain uses a good practice with a data annex, and Germany and Canada create their VNRs from an international cooperation perspective but show references to data.

Fiji and Samoa are not included in the Global Data Barometer yet, which may indicate a gap in available data or a limited focus on comprehensive data governance practices. Ghana’s scores are relatively lower across all modules, suggesting they must improve their data governance practices, especially regarding health. For all three countries, the references to data in the VNR come primarily in a narrative form, suggesting another relationship between reporting practices and data governance practice as measured by the Global Data Barometer.

Global Data Barometer climate moduleCanada’s, Germany’s, and Bangladesh’s scores indicate that they have expended significant efforts in this area and show a specific emphasis on managing and utilizing data for climate-related challenges. The ranking of these countries is primarily based on three critical indicators: vulnerable species, biodiversity, and emissions (This latter indicator is also one of the most reported indicators for SDG 13).

Looking at the evidence from Germany, we observe that data on emissions is available on the website of the National Environment Agency (Umwelt BundesAmt). It seems that some individual datasets are available on the open data portal of the German Government GovData.de. The same datasets are also available on the database of the Federal Office for Statistics (Destatis).

In the case of Canada, it is possible to find reports on greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, including emissions from land use activities and from large facilities. Every year, Canada prepares and submits a national greenhouse gas (GHG) inventory to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

It is noteworthy that there are data on gas emissions in open format on different government websites. It would be ideal if the VNRs could directly cite this information in its open format, which is easily accessible, comparable and can be reused to add public value to conversations around this important topic.

Global Data Barometer Healthcare moduleThis module covers civil registration and vital statistics (CRVS), COVID-19 testing, and the provision of primary health care, as its key indicators. The vital statistics data are included in the healthcare module of the GDB and the same indicators, which are also some of the most reported SDG indicators.

There is significant variation in the associated healthcare data performance across countries. Germany, Spain and Canadá have high scores indicating advanced healthcare data governance practices. On the other hand, the Dominican Republic and Ethiopia have lower scores, pointing towards potential areas for improvement in their healthcare data policies.

A review of national reporting platforms shows how these scores reflect country practices: For example, in the case of Germany, the Federal Office of Statistics Destatis and its database Genesis provide datasets on birth and death in separate detailed datasets.

In Canada, civil registration of births, marriages and deaths are managed at a provincial and territorial level, while national statistics are the responsibility of the federal agency – Statistics Canada. To access records, one should consult the respective local website or office. Statistics Canada maintains non-public databases for birth, stillbirth and death, subject to confidentiality restrictions, with data collected from provincial and territorial partners, and conducts studies and statistics that are available online.

In the case of Spain, we observe that on the national statistics website, information about the birth and death rate can be found, including basic statistical information related to the sex, age and place of the birth or death and also the cause of death. The death and birth information on the national statistics website is prepared in collaboration with the autonomous regions and different civil registries and although it is not published in the local official language, information can also be found on regional sites.

As with climate data, it would be ideal if country VNRs could directly cite this information in open formats, which is easily accessible, comparable and can be reused to add public value.

Gender Data CompassThe Gender Data Compass provides a holistic evaluation of a country’s gender data system, encompassing five points—availability, openness, foundations, capacity, and financing. This can help provide context to the VNR reporting on SDG 5 and gender data across all topics discussed in VNRs.

Table 5: Gender Data Compass scores

| Country | Gender Data Compass score |

| Colombia | 35 |

| Dominican Republic | 37 |

| Spain | 47 |

| Germany | 51 |

| Mongolia | 28 |

| Bangladesh | 20 |

| Canada | 54 |

| Samoa | 29 |

| Fiji | 17 |

| Ethiopia | 22 |

| Ghana | 30 |

Canada, for instance, despite its high ranking in North America, faces challenges in open data practices with 47 datasets assessed in the Compass not published under an open data license. Similarly, while Samoa leads in the Pacific Islands, most of its data is assessed under the GDC in a closed format or not published under an open data license. The Dominican Republic has a higher score than Colombia, but does not report on SDG 5 in its VNR.

Statistical strategies

All countries under review have implemented strategic frameworks to guide their statistical initiatives, reflecting a commitment to effective data management and dissemination. These strategies encompass a range of objectives, from transparency and open data to national statistical development plans. The strategic frameworks underline the countries’ systematic approaches to managing and utilizing statistical data for informed decision-making and policy development.

Germany, for instance, has a comprehensive statistical strategy accessible through the platform “govdata.de“, complementing the open data strategy, the e government law and the access to information law.

The Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) is governed by the Statistical Service Act of 2019, (Act 1003) which established it as an autonomous Public Service institution with a Board of Directors who report directly to the Office of the President. Currently, the data strategy is presented in a Corporate Plan (2020-2024), which provides a forward looking and international benchmarking framework to reposition GSS as the trusted provider of Official Statistics for good governance.

The UN Fundamental Principles of Official Statistics are not statistical strategies but form an important framing for many statistical systems. These principles have many points in common with the open data principles, as described by the UN Statistics Division. Statistical frameworks like the FPOS are essential for data management and dissemination and therefore complying with the FPOS can be seen as an indication of the ability of the fundamental governance pillars of the statistical system to produce and disseminate open data in the VNR. Indeed, the UNSD Guide for evidence-informed VNRs also sees the FPOS as a relevant piece of data governance for accountability, interoperability, timeliness, and interpretability, all of which open data supports. For 2023, SDG indicator 17.18.2, which tracks the compliance of statistical laws with FPOS, identifies all countries except Bangladesh and Dominican Republic in compliance. Ghana is an example of a country whose statistical law until recently was not in compliance; even though changing statistical laws is difficult, change is possible and can contribute to a better institutional setting for pursuing open data, including for SDG reporting.

Summary

Nearly all countries have completed at least one VNR and the 2024 round will see a further 37 countries report on SDG implementation in their country. Based on an initial review of 11 countries’ VNRs in the last four years, countries generally follow best practices by employing statistical annexes in their VNRs. However, there remains considerable room for improvement in the way these annexes are utilized. In addition, a significant issue is that countries often fail to cite the data sources within their VNRs, which undermines both the accessibility and transparency of the information provided. This lack of citation hinders stakeholders’ ability to verify the data and undermines the credibility of the reports.

Furthermore, the open data policies adopted by governments overall is not always reflected in their SDG reporting as shown by their VNRs. Lower middle and upper middle-income countries, however, tend to show greater coherence between their open data policies and their SDG reporting by their inclusion of many datapoints, statistical annexes, and recognition of open data as an important principle for official statistics. These countries likely have stronger incentives to present a favorable impression of their investment environment, which may drive them to align their policies more closely with their reporting practices and ensure that their VNRs are both comprehensive and transparent.

All countries, however, can benefit from building greater coherence to their domestic open data and their international reporting efforts and this paper lays out several recommendations. Future work aims to further generalize these findings by studying more countries and diving deeper into the country preparations of VNRs.

Recommendations

- Know the audience of the VNRs: It is understandable that VNRs are written in a narrative form for policymakers and international development exports. However, given the potential audience for VNRs could include civil society as well, countries should adopt existing guidance on employing visual aids to tell a diverse set of stories.

- As UNSD recommends, add an annex page focused on the SDG indicators used for reporting purposes: this will ease the burden of overwhelming the VNR with too much data. By incorporating both strong narratives and easy to find and navigate data annexes, countries can make their data easier to understand and find for citizens and researchers.

- Use open data available from national open data portals in VNR reporting for relevant indicators to improve reuse and value of data.

- Be detailed with citations: avoid crediting entire ministries instead of detailed publications or datasets. Avoid detailed acronyms as sources without explanation. When no links are provided, add a detailed bibliography. This will help users find the original source of data and help improve the transparency of VNRs.

- Adopt a government open data policy. Open data policies are associated with better VNR reporting practices, making them a useful tool to improve VNR reporting in any country. In addition, creating active transparency commitments or policies to specific SDG areas can motivate sectoral coordination on SDG reporting.

- Bring VNR reporting in line with open data and open government standards that have already been adopted by the government. Use VNRs as demonstrations of the ability of the government to coordinate on data collection and dissemination, which can help inform national efforts to adopt more open data policies and standards. This agrees with existing UNSD guidance that “countries must communicate openly and understandably to ensure effective reporting.” This could, for example, include collaboration and coordination between government transparency offices, statistics offices, and SDG focal points.

Authorship and Acknowledgements

This paper was authored by Renato Berrino Malaccorto at Open Data Charter (ODC), Lorenz Noe and Tawheeda Wahabzada at Open Data Watch (ODW). We would like to thank the reviewers Deirdre Appel, Jahanara Saeed, and Francesca Perucci (ODW), Mercedes de los Santos and Natalia Carfi (ODC).

Endnotes

[1] The share of all SDG 3 indicators that were classified as Tier I, meaning a well-established methodology with a significant number of datapoints for the majority of countries, was just below 50% at the start of the SDG period. Today this number is at just below 90%. There has been progress as well for SDGs 5 and 13, but both lag behind: As of March 2024, the share of Tier I indicators among Goal 5 indicators is 50% and among Goal 13 indicators is 38%. Analysis by Open Data Watch June 2024.

[2] South Sudan and Yemen are counted as part of the 189 countries, as they have signaled their intent to submit their first VNR at the High-level Political Forum in July 2024. See the full list of countries who have submitted a VNR by year here: https://hlpf.un.org/countries

[3] According to the Open Definition, “open means anyone can freely access, use, modify, and share for any purpose (subject, at most, to requirements that preserve provenance and openness).” https://opendefinition.org/

[4] The Open Data Charter and its principles were developed in 2015 by governments, civil society, and experts around the world to represent a globally-agreed set of aspirational norms for how to publish data. https://opendatacharter.org/principles/

[5] Researchers reviewed text referring to SDG indicators related to Goals 3, 5, and 13 in VNRs accessible here for the following countries and VNR years: Asia: Mongolia (2023) and Bangladesh (2020); Americas: Canada (2023), Colombia (2021), and Dominican Republic (2021); Europe: Germany (2021) and Spain (2021); Oceania: Samoa (2020) and Fiji (2023); Africa: Ethiopia (2022) and Ghana (2022).

[6] And 64% based on the 2023 round of VNRs according to the 2023 VNR Synthesis report https://hlpf.un.org/sites/default/files/2023-12/2023_VNR_Synthesis_Report.pdf

[7] A data point is defined in this exercise as any number or statistic relevant to the SDG Agenda as part of the VNR text. For example, researchers looked for sentences like “The number of new HIV infections dropped from 5 per 1000 to 3 per 1000.” This would be counted as one data point. Similarly, a table or graphic in the VNR would count as one datapoint.

[8] OGP has highlighted policy areas in its work related to the three SDGs studied in this brief: Gender (including feminist open government initiatives from member countries, a toolkit for more gender-responsive action plans, and research resources, etc.); Environment and Climate (exploring how open government approaches can support ambitious and equitable climate actions that are backed with the political will and institutional capacity to implement them); and Health (exploring how governments build stronger healthcare systems through open data and participatory, accountable public decision-making).

[9] Information that governments have to publish without a request for access to information, like budget information, assets declarations, public procurement information, etc.

[10] Examples include Spain with a robust open data initiative, in Germany it is covered by the open data strategy and the e-government law and the country has a centralized portal, in Colombia the Law 1712 of 2014 on Transparency and Access to Public Information establishes a framework for the application of guidelines and good practices in the development of strategies for openness and reuse of open data and it also has a centralized Open Data Portal, and the Dominican Republic developed a standard and policy as well as an Open Data Portal.