View or download the PDF print version

View this research brief at Data2x

Filling the Financing Gaps:

Domestic Resourcing in National Gender Data Systems

INTRODUCTION

Domestic financing for gender statistics is central to producing high quality data, and therefore essential to achieving gender equality. Low- and middle-income countries face tightening international assistance budgets for data and statistics, exacerbating an already volatile and insufficient source of support. Well-resourced statistical systems ensure the collection, analysis, and dissemination of accurate and comprehensive gender-disaggregated data, essential for informed policymaking and measuring gender equality progress. Establishing sustainable domestic financing is therefore crucial to foster resilient systems needed to support long-term commitments to gender equality.

The mechanism by which gender data are funded is often opaque. But planning documents can offer some insight into how gender data fits into statistical systems and planning. To improve the awareness of global and country gender data advocates about the ways in which gender data financing takes place worldwide, Open Data Watch examined the state of domestic resourcing for gender data based on statistical planning documents for Data2X. Reviewing financial plans and requirements for gender data provides insights into the sustainability and autonomy of a nation’s statistical initiatives, gauges vulnerability to external funding fluctuations, and illuminates political priorities in a country’s gender equality agenda. In concert with insights on ODA, political will, and gender data systems assessments, this knowledge can support advocacy, donor and other resource allocation, and collaboration.

We reviewed all publicly available plans covering national statistics (National Strategies for the Development of Statistics (NSDS) or country-equivalent). Only 30 percent of all countries include detailed budgets in their statistics plans, and only two-thirds of these include allocations for gender data. Countries with specific line-item allocations to gender data in their statistical plans are the focus of this work as they are assumed to give greater importance to gathering and using gender data. Our analysis was ultimately limited to 42 documents from 39 low- and middle-income countries with specific allocations for gender data.[1] These documents provide a sense of the policy priorities and funding needs around gender data in select countries, but this analysis does not examine actual budgets or expenditures of national statistical offices (NSOs). Please see the Annex for additional details on our methodology.

The rest of this brief will answer questions around what gender data funding is allocated to, what the source of funding is, who implements the gender data activities, and what challenges have been identified by countries.

WHAT IS FUNDING FOR GENDER DATA ALLOCATED TO?

Each government is responsible for collecting official statistics relevant to its country to inform policies. The responsibility of financing these efforts, including for gender data, also lies with governments. In many contexts, external donors play a supporting role in financing data collection activities. For gender data, this role is small indeed: Low- and middle- income countries receive an average of only 11 US cents per capita from external donors for gender data, compared to $1.40 per capita for all data. Whether external support for gender data is plentiful or scarce in a country’s context, NSOs and other gender data focal points in government need to look for where scarce domestic resources can be allocated most effectively for gender data and work with budgeting processes to ensure support to gender data is consistent and sufficient.

STRATEGIC EMPHASIS

Amid this funding shortage, countries need to set their own agendas given the funds they can reasonably expect to receive based on past domestic and external funding rounds. NSOs structure their work programs around goals or areas of work that guide their activities over the period of the NSDS. These overall areas of work are called “objectives” for the purpose of this analysis to distinguish them from “activities,” which constitute the actual projects that are planned to achieve the objectives. Thirteen of the 39 countries studied include an objective for gender data and accompanying activities in their plans. The inclusion of a gender data objective implies a comprehensive approach, not only in recognizing the importance of gender data but also in delineating specific actions to achieve set objectives. These objectives range from gender mainstreaming to improving statistical production through enhanced coverage and disaggregation.

Among these countries, the prevalent focus on disaggregation by sex or gender underscores the importance of incorporating gender perspectives across various statistical domains. The inclusion of gender data as part of open data initiatives, like that of Equatorial Guinea,[2] reflects a commitment to transparency and inclusivity. The emphasis on the development and modernization of gender data in Ghana and Senegal demonstrates the integral role of gender in advancing broader efforts to enhance statistical systems.[3],[4]

Most other countries in this study identify gender data activities in one or more places in their budget but without an overarching gender data objective as part of their plan for the implementation of the NSDS, suggesting that better gender data may not be prioritized as much as other statistical topics. The singular case of Burundi, with an objective accompanied by funding but lacking specific activities with funding, underscores the need for a more transparent and action-oriented framework.[5] Generating better gender data to support efforts to achieve gender equality requires acknowledging the importance of gender data and also a clear roadmap with well-defined activities to drive meaningful change and progress.

PLANNED ACTIVITIES

Activities are defined as the projects that are planned to achieve overall objectives in a statistical plan. There is significant variation in what is funded at the activity level. Around one-third of countries with activity-level information mention general efforts to conduct more sex- disaggregated surveys. Another five countries note a general collection of gender data during data production. Creating an index or tool to measure gender equality, alongside fact sheets, is also an activity that a handful of countries are pursuing. Other examples include identifying data sources (Bangladesh),[6] strengthening the institutions/agencies responsible for gender data (Vanuatu),[7] and arranging/conducting workshops with data providers and users (Malawi).[8]

Gender data use is most often talked about in terms of the NSO using gender data to develop gender-relevant indicators from the data, and then publishing, disseminating, and spreading awareness of gender data among NSO staff, other members of the National Statistical System (NSS), or civil society mostly in the form of trainings, workshops, attractive knowledge products, and open data. For example, in Ghana the specific objective to “enhance dissemination and communication and use of gender statistics” has two activities attached to it: One to identify and use promising channels for communication and dissemination of gender data and another to engage users and producers in feedback sessions.[9] This is to be implemented by the Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) in collaboration with several working groups within the NSO and external partners such as the Ministry of Communications and mobile-telephone organizations at a combined cost of $1.1 million over five years (no detail of sources of funding is provided).

The finding that most countries with funding for specific gender data activities primarily concentrate on data production in their policy priorities, with very few emphasizing the publication and dissemination of gender data, or use in policymaking, suggests a potential imbalance in addressing the entire data lifecycle. This inclination may stem from the prevailing challenge of substantial gender data gaps, but nevertheless it emphasizes the need for increased attention to effectively using gender data.

Although data use receives some funding in existing NSDSs, such as for user-producer dialogues (Kenya),[10] workshops on the importance of gender data use (Malawi),[11] and user mapping for statistical products (Paraguay), broadening financial support to encompass the entire spectrum of gender data activities, from production to meaningful use, is crucial to ensure the full value of gender data is realized.[12]

WHERE DOES FUNDING COME FROM?

Just under half of all plans for data financing with gender allocations include estimates of how much of each objective or activity is expected to be raised from external or domestic sources, as well as estimates of how much funding has been secured and how much is still outstanding. The definitions of each of these categories vary by country but within NSDSs that note a split between internal and external funding, anywhere from none to all funding comes from domestic resources, with an average of 44 percent and a median of 34 percent. This large range and the different definitions of domestic funding (secured or unsecured) should lead to caution when interpreting these numbers.

However, the above numbers do reveal that most countries with gender data in statistical plans rely on external funders to fund more than half of all gender data activities. Examining several countries helps to characterize this range beyond these headline numbers. Kenya has a very detailed plan for gender statistics but does not publish this information, instead restricting itself to the statement that domestic funding for gender statistics is an issue because “most of the budget for gender statistics (80 percent) is donor-funded.”[13] Ghana and Paraguay, even though they are two of the only other countries with specific gender data plans, do not provide any breakdown.

Other countries, however, provide a detailed breakdown of internal and external funding, but with varying levels of specificity and consistency. For example, there are ten activities listed by Senegal under “production of gender-sensitive statistics,” of which all but one is to be fully funded by external development partners. The one exception is the creation of the national directory of women entrepreneurs, for which the state will contribute 10 percent of the funding.[14] Furthermore, there are four activities listed under the budget item carrying out gender studies: “carrying out a study on the political participation of women; carrying out a study on disparities and discrimination in laws and regulations on gender; completion of the study on the gender audit of three ministries (Women, Microfinance, Interior); [and] production of the [Sustainable Development Goals] synthesis report.” The first three are to be funded fully by donors and the fourth is costed but funding not yet secured.[15] All additional gender data activities in Senegal’s plan, such as one on establishing a gender-based violence survey, are either also fully funded externally or are still to be funded from either source.

Ethiopia dedicates an entire sub-theme to gender mainstreaming, with activities on gender data disaggregation for major economic sectors, conducting time use surveys periodically, investigating existing datasets for gender data, conducting gender asset gap surveys, and strengthening the functions of the gender mainstreaming directorate. Of these, only the surveys and data mining from existing surveys have been costed and are to be fully financed by donors. Notable exceptions to the pattern of gender data activities being assigned to donor funding are the Republic of Congo[16] and Equatorial Guinea, which intend for the national government to provide more than 90 percent of funding for gender data activities.[17]

WHO IS INVOLVED IN GENDER DATA ACTIVITIES?

In addition to knowing sources for gender data financing and what activities they support, it is important to know which agencies will receive gender data financing and which are active in the implementation of gender data activities, something identified by many countries as a challenge for their data and statistics programs overall. The NSDSs cannot confirm how much funding each ministry will receive from the treasury or donors. However, knowing which actors are involved in gender data activities and therefore receive funding for gender data allows us to build out an ecosystem of national actors involved in gender data for official statistics.

Since the composition of gender data financing stakeholders is unique to each country, what follows is the non-exhaustive list of the main organizations involved in gender data according to NSDS or gender data plans in Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, Paraguay, and Senegal. This list reveals that the most common stakeholders involved in gender data activities, outside the NSO itself, is a gender-relevant office, either a ministry dedicated specifically to gender equality, or an office concerned with social affairs.

Table 1: Gender Data Financing Stakeholders

COUNTRY STAKEHOLDERS AND ACTIVITIES

| Burkina Faso | ■ NSO (INSD) in collaboration with regional stakeholders mentioned for gender booklets. ■ NSO to work with gender ministry (Ministère de la Femme, de la solidarité nationale, de la famille et de l’action humanitaire) on gender dashboard. ■ NSS and interior ministry (Ministry of Security) to work on gender-based violence statistics. |

| Ethiopia

| ■ NSO (Central Statistics Agency) and special gender government task force (Gender Mainstreaming Directorate) for all activities. |

| Ghana

| ■ NSO (Ghana Statistical Service) and gender ministry (Ministry of Gender, Children, and Social Protection) are primary authors and actors. ■ Line ministries, as well as subnational entities (Municipal and Metropolitan Assemblies) for gender fact sheets and statistical capacity strengthening and monitoring. ■ Telecommunications ministry (Ministry of Communications) and private sector companies (mobile-telephone organizations) for enhancing dissemination, communication, and use of gender statistics. ■ Health ministry (Ministry of Health) for health statistics. |

| Kenya

| ■ NSO (Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS)) and special gender government task force (the State Department for Gender (SDfG)), and the National Gender Equality Commission (NGEC) authored gender statistics plan.■ SDfG helps with gender data capacity in partnership with KNBS and NGEC and helps provide oversight for reporting gender data from line ministries. ■ In addition, the Gender Sector Working Group, a stakeholder group on gender equality programs with state and non-state actors, will be part of the envisioned Inter-Agency Gender Statistics Technical Committee |

| Nigeria | ■ Gender statistics training program supported by the NSO (National Bureau of Statistics), subnational entities (State Bureau of Statistics), and line ministries. Cost split is roughly 1:2:1, respectively. |

| Paraguay

| ■ NSO (INE) and gender ministry (Ministerio de la Mujer) are the major coordinators. Within the gender ministry, specifically Observatorio de Género and administrative registers. ■ Social ministry (Ministry of Social Development), education ministry (Ministry of Education and Science), and finance ministry (Ministry of Finance) are supposed to be involved in activity around formation of a group of key authorities for decision-making and advocacy on gender statistics that can act as an audience for special training and statistical dissemination program that includes specific modules on gender statistics. |

| Senegal | ■ NSO (ANSD) activities throughout on gender data. ■ Special gender government task force (Direction de l’Egalité et de l’Equité de Genre) responsible for gender thematic reports and review report of gender activities. ■ Gender ministry (Ministère de la Femme, de la Famille, du Genre et de la Protection des Enfants) responsible for institutional plans for gender data and gender representation survey among ministries. ■ Special gender government task force (Observatoire National de la Parité) responsible for surveys and microdata on attitudes and metadata. ■ Special gender government task force (Direction des Organisations Féminines et de l’Entreprenariat Féminin) responsible for national survey on female entrepreneurship. |

WHAT CHALLENGES ARE IDENTIFIED BY COUNTRIES?

In this section, we examine how countries describe the weaknesses of their financing for data and statistics, as well as gender data specifically. Traditionally, most NSDSs contain some version of a Strength, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats (SWOT) analysis. Close to 90 percent of the countries in our sample feature some analysis of strengths and weaknesses.

Twenty-five countries identify funding to all data and statistics as a key threat or weakness, whether due to a lack of funding, reliance on outside funding, or inconsistent funding. Thirteen countries specifically noted their reliance on outside funding as a threat or weakness.[18] Only one country, Mozambique, noted that increasing financing of official statistical activity by the state as a strength of its system, but it still flagged strong dependence on external financing as a weakness.18 Other issues mentioned were overall low levels of funding, increasing cost of operations, low salaries for staff, and new areas of work (such as data mining, visualization software, and geospatial data) that are not being invested in.

Many countries also noted coordination with both domestic stakeholders and international partners as challenges in a complex data landscape. Effective coordination can enhance the efficiency, quality, and reliability of gender data activities and maximize the value and deployment of limited funding resources. In turn, additional funding can also be deployed to support greater coordination and management. Addressing these twin challenges of funding constraints and coordination difficulties is essential to fortify national statistical capacities and foster a more harmonized and connected global data ecosystem.

CONCLUSION

This review of statistical plans with a gender data lens emphasizes the importance of transparency, a virtuous cycle between gender data production and use, and coordination among actors in the gender data ecosystem.

Enhancing transparency in plans and budgets is crucial, particularly for gender data. This transparency is not only beneficial for agencies engaged in statistical capacity building, allowing them a clearer view of activities within the national statistical system, but it also empowers citizens and advocates to hold governments accountable. Furthermore, it enables international donors to coordinate their support more efficiently.

Incorporating a focus on gender data production within the objectives of statistical plans is essential, considering the significant gaps in gender data. However, the emphasis should not only be on production but also on the use and impact of this data. Creating a virtuous cycle in which gender data is both produced and effectively used is key.

The importance of coordination within the NSS and between the NSS and outside actors, like donors, must be underscored. Effective coordination improves the efficiency, quality, and reliability of gender data activities, which in turn can attract more funding. This is especially true when efforts are combined between various external funders. Funders themselves play a critical role in promoting better coordination through their funding mechanisms, ensuring the long-term sustainability of these initiatives.

With these important lessons in mind, this review has also revealed the range of possible future directions for research in this area to operationalize solutions for more sustainable gender data financing. There is a need for a deeper understanding of how actors within national statistical systems and planning departments direct funding flows to specific activities, particularly if funding comes from both domestic and international sources. NSDS evaluations and Country Reports on Support to Statistics (CRESS) could reveal crucial intervention points and identify influential actors. In addition, this research may benefit from a comparison between gender data prioritization in budgets and gender data outcomes, and a deeper and more qualitative analysis of what countries themselves identify as concerns or opportunities in their SWOT analyses, particularly in those countries that allocate resources to gender data. Additionally, a more focused investigation into the coordination mechanisms specifically for gender data, along with a study of selected country stakeholders and their collaboration on gender data activities, could provide valuable insights.

Ultimately each country’s statistical actors must be able to advocate for its funding based on its context. This brief has tried to aid these actors in their efforts by recognizing shared challenges and features of gender data financing across countries. The challenges countries face when building better gender data systems are many, but peer learning could be one way of providing solutions based on the experience of a similar context. At the same time, civil society organizations and external funders are encouraged to use these findings to inform more productive engagements with countries on statistical capacity building projects for better gender data.

ANNEX

WHAT COUNTRY PLANNING INFORMATION IS AVAILABLE?

Geographic availability

From our review of NSO websites and using existing resources such as PARIS21’s NSDS Status Summary Table, 136 countries and territories (35 high-income, 41 upper-middle, 40 lower- middle, and 18 low-income) publish national strategies for the development of statistics (NSDS) or similar plans such as corporate plans or annual plans for the statistical system.[19] The remaining 60 countries are those without NSDS-type plans, including 14 countries that have strategies but do not publish them as accessible documents. Half of the countries without published plans are high-income, four are low-income, and 26 are middle-income countries.

Timeliness

Of the 136 countries, nine do not have a year associated with their plans, but of the remaining 127, one-third (45 countries) have expired plans, meaning the plan covers a period before 2023. Nineteen countries’ plans expired in 2023. Planning for statistics presents its own challenges, requiring capacity and financing that should not take away from ongoing efforts to produce data and statistics. The COVID-19 pandemic led to overdue plans for this cohort, as plans that would have normally expired still apply because the work was paused.

Gender mainstreaming

Encouragingly, over 70 percent of the available statistical plans make some mention of gender and its importance in the document. But it is one thing to mention gender as one of the components of the Sustainable Development Goals and another to make it part of the work program for the statistical system. Although 45 percent of NSDSs have line-item tasks on gender data (not necessarily budgeted), only 12 percent of NSDSs fully mainstream and integrate gender throughout the strategy. Mainstreaming gender data goes beyond listing items in a budget: It involves the recognition of why gender data are important, including gender throughout the plan and budget, and emphasizing the need for better production and use of gender data.

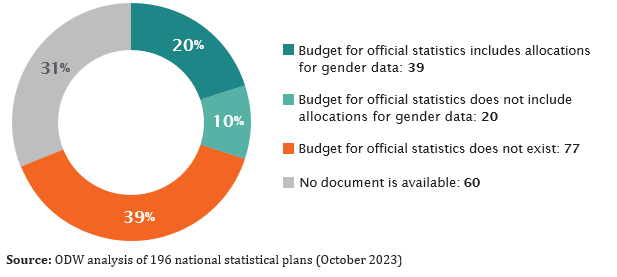

Across all 196 countries (with or without plans), only 30 percent have a detailed budget for statistics. Of those, two-thirds (39 countries) have a budget with allocations for gender data. However, this only represents 20 percent of all countries due to the lack of statistical plans and budgets for most countries.[20] This illustrates the need for more transparent information on financing for statistics published by countries.

Figure 1: Availability of Budget Figures in Statistical Plans

Endnotes

[1] Kenya, Ghana, and Paraguay have both an overall NSDS and a specific gender data plan.

[2] Estrategia Nacional de Desarrollo de la Estadística de Guinea Ecuatorial 2022-2026.(2023). https://inege.org/ wp-content/uploads/2023/09/ENDE-2022-2026-1.pdf

[3] Ministry of Gender, Children, and Social Protection. (2021). Ghana: Five Year Strategic Plan for Gender Statistics (2018-2022). https://www.mogcsp.gov.gh/mdocs-posts/five-year-strategic-plan-for-genderstatistics/

[4] Conseil National de la Statistique. (2019). Senegal: Troisième Stratégie Nationale de Développement de la Statistique (SNDS III 2019-2023). https://smartdatafinance.org/storage/2021-09-28/ Lz84pK3Twh8ZGzX.pdf

[5] Ministere a la Presidence Charge de la Bonne Governance et du Plan. (2016). Deuxième Stratégie Nationale de Développement de la Statistique au Burundi (SNDSB-II), pg. 67. https://afristat.org/wpcontent/ uploads/2022/04/3_Burundi_Document-Principal-2-2016-2020.pdf

[6] Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. (2015). Bangladesh National Strategy for the Development of Statistics (2013-2023), pg. 83. https://www.paris21.org/sites/default/files/Bangladesh%20NSDS_2013-23_ Final%20Cabinet%20approved.pdf

[7] Vanuatu National Statistics. Vanuatu National Strategy for the Development of Statistics: A Strategy for the Agenda Building Capacity in Statistics 2016-2020, pg. 44. https://vnso.gov.vu/images/Special_ Report/NSDS/NSDS.pdf

[8] Malawi Government. (2020). National Statistical System Strategic Plan 2019/20 – 2022/23, pg. 45. http://www.nsomalawi.mw/images/stories/NSSACTIVITIES/national%20statistical%20system%20 strategic%20plan%202019-2023.pdf

[9] Ministry of Gender, Children, and Social Protection. (2021). Ghana: Five Year Strategic Plan for Gender Statistics (2018-2022), pg. 93. https://www.mogcsp.gov.gh/mdocs-posts/five-year-strategic-plan-forgender- statistics/

[10] Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. (2020). Kenya Gender Sector Statistics Plan, pg. 41. https://new. knbs.or.ke/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Gender-Sector-Statistics-Plan.pdf

[11] Malawi Government. (2020). National Statistical System Strategic Plan 2019/20 – 2022/23, pg. 45. http://www.nsomalawi.mw/images/stories/NSSACTIVITIES/national%20statistical%20system%20 strategic%20plan%202019-2023.pdf

[12] Instituto Nacional de Estadisticia. (2021). Estrategia De Estadísticas De Género, Paraguay 2021-2025, Resultado 3.1, pg. 30. https://www.ine.gov.py/Publicaciones/Biblioteca/documento/eda7_EEG%20 PRY%202021%20-%202025.pdf

[13] Kenya Gender Sector Statistics Plan page 22.

[14] Senegal SNDS III, page 115-116.

[15] Senegal SNDS III, page 112.

[16] Republic du Congo. (2023). Strategie Nationale de Developpement de la Statistique (SNDS 2022-2026), pg. 32. https://www.afristat.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/SNDS_2022-2026_Congo.pdf.

[17] Republica de Guinea Ecquatorial Consejo Nacional de Estadistica. (2023). Estrategia Nacional de Desarrollo de la Estadística de Guinea Ecuatorial 2022-2026, pg. 89.

[18] Republica de Mocambique Conselho Superior de Estatistica. Plan Estrategico do Sistema Estatistico Nacional 2020-2024, pg. 16. https://www.ine.gov.mz/documents/d/guest/pe-sen-2020-2024–corrigi do%3Fdownload%3Dtrue&ved=2ahUKEwj_9M309YCGAxWCKlkFHTnpBD4QFnoECBMQAQ&usg=AOvV aw08jUqvEQW6F1k7V6XppOoq

[19] FY24 World Bank income groups. Of the 136 countries, 2 are not categorized by income by the World Bank (Anguilla and Venezuela).

[20] Allocations to gender data means any line items in budgets that specifically mention gender, sex, women/men, or disaggregation.