View or download the PDF print version

View this research brief at Data2x

Filling the Financing Gaps:

Development Assistance for Gender Data Systems

INTRODUCTION

Reliable and nuanced gender data are critical to identifying and addressing gender disparities. With these data, policymakers and advocates can craft targeted, effective policies and interventions to address gender issues, monitor progress, and hold governments accountable. However, collecting and analyzing high-quality gender data is challenging in the absence of adequate funding. While domestic resourcing is ideal as it is long-term and sustainable, external financing can be a crucial source of funding for gathering gender data and ensuring its accessibility and usability for informed decision-making, which can ultimately support gender equality initiatives.

This paper uses data on Official Development Assistance (ODA) from the Clearinghouse for Financing Development Data, also published in PARIS21’s annual Partner Report on Estimating Support to Statistics (PRESS). Open Data Watch analyzed this dataset for Data2X, focusing on individual transactions for ODA projects marked as relevant to gender data.[1] The Annex summarizes this methodology. All dollar amounts are in constant 2021 US Dollars.

Gender data financing is part of the dynamic landscape of ODA disbursements for overall data and statistics, which is marked by a notable rebound in funding to near pre-pandemic levels. According to PRESS2023 there was a 14 percent increase in funding for data and statistics in 2021, bringing the total to approximately $800 million. This resurgence is largely attributed to multilaterals, which increased spending by 77 percent since 2018, compensating for the third consecutive year of decreasing bilateral funding. Grants remain the predominant form of funding for data and statistics, offering twice as much support as loans. But grant funding remains flat; the increase in funding for data and statistics instead is coming from loans. Whether or not multilateral efforts are intentionally filling gaps left by bilateral donors, the need for increased funding for data and statistics, including gender data, is clear based on a previous analysis estimating a funding gap of $700 million.

FUNDING FOR GENDER DATA

Total funding to gender data as of 2021 (the last year of complete project-level data) was $122 million dollars, the highest amount tracked for this metric yet. But this single number reflects changes in the overall landscape.[2] Representing 15 percent of all data and statistics financing, 2021 funding for gender data was higher than average for the past decade (12 percent), though still slightly lower than the peak of 16 percent in 2015. Additional analysis of this comparatively high level of financing for gender data complicates the impression of progress.

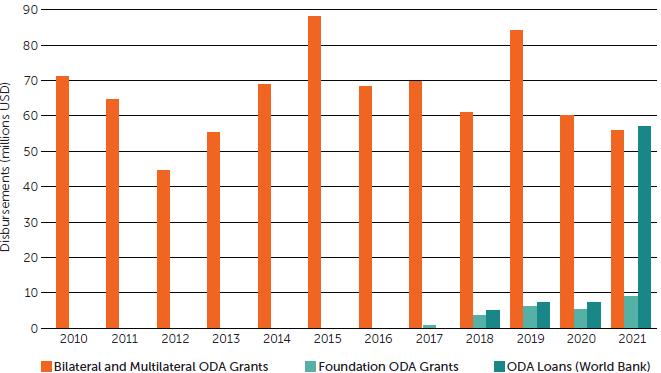

Figure 1 shows the overall financing for gender data since 2010 by source. Although the high point of funding in 2021 for gender data financing tells a story of higher levels, a deeper look at 2021 funding reveals that this peak is driven by a spike in loan financing from the World Bank, specifically for a project in Nepal to build a Civil Registration system.[3] The World Bank is the only donor using loans in addition to grants to finance gender statistics, with all others financing gender statistics through grants alone. Setting aside the World Bank loans, the overall picture for gender data financing remains one of stagnation.

Figure 1: Financing mechanisms for gender data 2010-2021

Source: ODW analysis of Clearinghouse for Financing Development Data dataset (Nov 2023)

TOP DONORS TO GENDER DATA

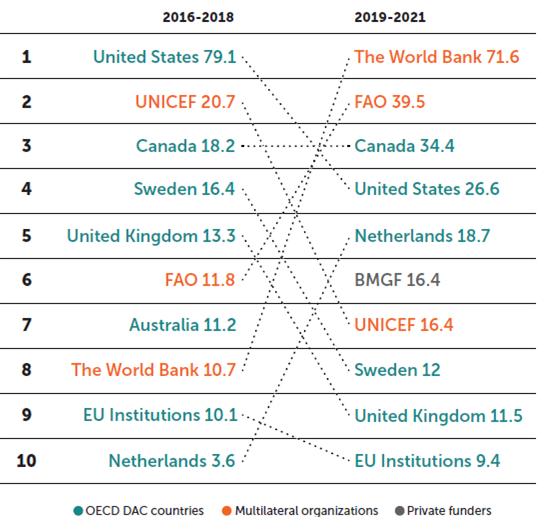

The profile of the top donors has shifted from the start of the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) era to now, with increased focus on comprehensive measures of development outcomes, including gender data (Figure 2). Multilateral organizations are more represented on the list of top donors. In 2016-2018, three-quarters of all financing for gender data came from the main bilateral donors of the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) funding, mostly through grants.[4] More recently (2019-2021), with increasing funding from new types of donors (like private foundations) and different types of financing (like loans), bilateral DAC grants are now less than half of all financing. Multilateral sources provided 46 percent and foundations, led by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, an additional seven percent.

Figure 2: Top 10 donors to gender data and USD million disbursements from 2016-2018 to 2019-2021[5]

Source: ODW analysis of Clearinghouse for Financing Development Data dataset (Nov 2023)

Two multilateral organizations (the World Bank and Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)) significantly increased their disbursements to gender data financing, while the total from DAC countries remained stable, though individual country contributions changed. The United States, Canada, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands are useful examples of this change in composition: All five are consistently among the top 10 of donors over the past six years but their disbursements have either significantly increased (Canada, Netherlands), decreased (United States, Sweden) or stayed about the same (the United Kingdom). Yet all remain among the top 10 donors and vital to future funding for better gender data.

TOP RECIPIENTS OF GENDER DATA FUNDING

Individual country disbursements in 2019-2021 rarely exceeded $2 million, except for a few large projects, such as the World Bank’s project in Nepal (Table 1). Only 27 individual countries received gender data financing disbursements in 2019-2021 while 31 did so in 2016-2018. At the same time, financing for regions (multi-country) or unspecified recipients (multi-country across regions) constituted 44 percent of all grants and loans for gender data, an increase from 34 percent in 2016-2018. This largely matches the overall trend in funding to data and statistics, which is moving away from funding individual countries.[6]

Table 1: Recipients of over $2 million USD of gender data financing in 2019-2021 and 2016-2018

| RECIPIENT | DISBURSEMENT 2019-21 (MILLIONS USD) | DISBURSEMENT 2016-18 (MILLIONS USD) |

| Bilateral, unspecified* | 90.7 | 48.7 |

| Nepal | 74.1 | 7.5 |

| Tanzania | 20.0 | 13.5 |

| Africa, regional* | 9.0 | 7.1 |

| Americas, regional* | 6.4 | 2.7 |

| South of Sahara, regional* | 6.4 | 1.2 |

| Ethiopia | 6.2 | 6.1 |

| Asia, regional* | 5.5 | 4.9 |

| Mozambique | 5.1 | 7.1 |

| India | 4.8 | 4.5 |

| Madagascar | 3.4 | 1.1 |

| Nigeria | 3.2 | 3.5 |

| Somalia | 3.1 | 1.5 |

| Oceania, regional* | 3.0 | – |

| Nicaragua | 2.9 | 1.7 |

| Pakistan | 2.8 | 4.8 |

| Burkina Faso | 2.5 | 1.8 |

| Senegal | 2.5 | 3.7 |

| Guinea-Bissau | 2.1 | – |

*Regional recipients

Source: ODW analysis of Clearinghouse for Financing Development Data dataset (Nov 2023)

GENDER DATA AND GENDER EQUALITY FUNDING

PRESS2022 revealed a divergence between funding for gender data projects and gender equality projects. The latter have been on an upward trajectory, more than doubling in commitments since 2010 and reaching close to $60 billion annually.[7] Funding for gender data, except in 2021, does not match this growth, indicating that data are not automatically included as a share of gender equality projects. Furthermore, this overall trend hides examples of where funding for gender equality is matched by funding for gender data, which can be used to make the case for best practices for funding gender equality and gender data together.

Table 2 shows the top bilateral DAC donors by their total funding commitments to gender data over 2019-2021, their share of gender data commitments in all data commitments, their total gender equality commitments, and their share of gender data commitments in gender equality commitments. Commitments are used rather than disbursements as only commitments to gender equality by DAC countries are captured in the OECD gender equality database. The ranking of top donors therefore varies from Figure 2 above. Donors also vary in how fast or how regularly they disburse commitments, further complicating analysis of these data.

Table 2: Measuring the alignment of donors’ gender equality funding (2019-2021)

| DAC DONOR | TOTAL COMMITMENTS TO GENDER DATA (MILLIONS USD) | PERCENT OF TOTAL DATA COMMITMENTS TO GENDER DATA | TOTAL COMMITMENTS TO GENDER EQUALITY (MILLIONS USD) | PERCENT OF GENDER EQUALITY COMMITMENTS TO GENDER DATA |

| Netherlands | 76.5 | 48.7 | 9,260.7 | 0.8 |

| United States | 39.5 | 7.5 | 18,360.1 | 0.2 |

| Canada | 34.5 | 13.5 | 10,443.0 | 0.3 |

| Germany | 12.3 | 7.1 | 32,184.1 | 0.0 |

| Sweden | 9.6 | 2.7 | 5,116.0 | 0.2 |

| Norway | 7.9 | 1.2 | 5,152.4 | 0.2 |

| Italy | 7.3 | 6.1 | 1,488.5 | 0.5 |

| Australia | 4.5 | 4.9 | 3,110.1 | 0.1 |

| United Kingdom | 2.4 | 7.1 | 13,093.7 | 0.0 |

| Spain | 1.5 | 4.5 | 1,105.9 | 0.1 |

| Ireland | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1,057.3 | 0.1 |

| EU Institutions | 0.8 | 3.5 | 31,054.5 | 0.0 |

| Austria | 0.6 | 1.5 | 479.6 | 0.1 |

| Belgium | 0.1 | – | 1,930.9 | 0.0 |

| Finland | 0.1 | 1.7 | 1,089.5 | 0.0 |

| Korea | 0.1 | 4.8 | 2,332.4 | 0.0 |

| France | – | 1.8 | 1,8912.5 | – |

| Switzerland | – | 3.7 | 4,338.8 | – |

Source: ODW analysis of Clearinghouse for Financing Development Data dataset (Nov 2023) and OECD database “Aid projects targeting gender equality and women’s empowerment (CRS)” (Nov 2023)

As shown in the third column, donors vary widely in their commitments to gender data and to data and statistics overall. For example, more than 60 percent of funding by Canada and the Netherlands for data and statistics is gender-relevant, while less than 20 percent of the United States’ is. Comparing commitments to gender data with commitments to gender equality (column five) reveals that overall funding for gender data remains low, less than a fifth of a percent on average. This is particularly pronounced for major donors of ODA for gender equality like Germany, the EU, and the United Kingdom. The Netherlands stands out from all donors with the highest share; gender data financing accounting for almost one percent of their gender equality commitments.

TOP GENDER DATA ACTIVITIES

Digging further into the activities funded as part of financing for gender data reveals more about the type of projects that donors support. The following findings are based on analysis of forthcoming data from the Clearinghouse for Financing Development Data that assigns activity markers to gender data projects.

During 2019-2021 there was a significant focus on population registers, accounting for almost a quarter of all gender data funding. This targeted investment may suggest a strategic commitment to obtain comprehensive demographic insights from administrative data, potentially laying the groundwork for more gender-specific data. This also represents a shift from the overall funding for gender data during 2011 to 2021, when support to household surveys was highest.

Health statistics emerged as the second most funded activity in 2019-2021, closely followed by social protection. Health and social protection are very relevant to individuals’ well-being, especially in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have also affected the shift of funding to population registers. Eight percent of gender data funding 2019-2021 was relevant to climate change, which may change as countries fund more of the $100 billion goal for climate finance for low- and middle-income countries. This is enough to make it one of the top five areas of activities for gender data, potentially indicating that donors are increasingly interested in the intersection of climate change and gender equality.

DONOR PROFILES

The donors that constitute the top contributors to gender data in 2019-2021 have different areas of focus and motivations. This section reviews individual activities and policies, where relevant, as a way of describing their gender data financing profile in more detail.

- Canada has been the largest bilateral donor to gender data in recent years, almost doubling disbursements from 2016-2018 to 2019-2021. Over 60 percent of this funding in 2019- 2021 was for birth registration specifically, or civil registration and vital statistics (CRVS) generally (which commonly includes birth, death, marriage, and divorce registration). In the preceding three-year period, CRVS funding constituted over 80 percent of their disbursements to gender data. Canada has increased absolute funding for CRVS while also diversifying into new areas. These include sexual and gender-based violence in post- conflict situations and online; one-time support for a large household survey; improving female labor participation rates; health information systems; and data systems for reproductive rights. Canada adopted a Feminist International Assistance Policy in 2017. Its considerable disbursements to gender data comprise over half of its total support to data and statistics, setting an example for other donors to harmonize gender equality goals and gender data support.

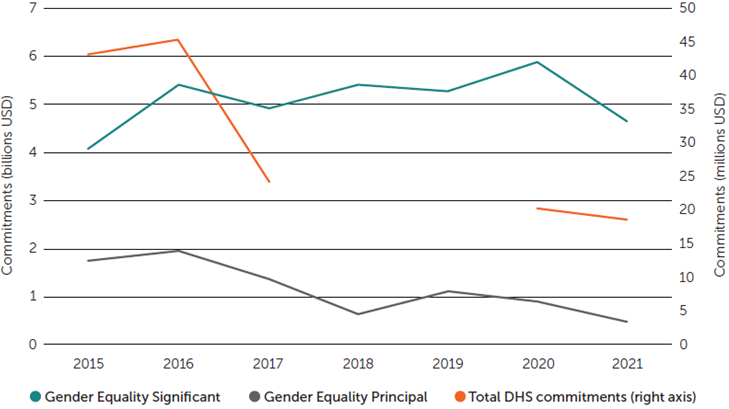

- The United States was the largest DAC provider of ODA in 2022 and has also been one of the largest providers of ODA for gender data over the past ten years. Yet its funding for gender data has decreased in the most recent three-year period. More than 90 percent of recent US gender data funding comes through its support for the Demographic and Health Survey program. Whether because of a decrease in funding or due to a change in reporting to the Creditor Reporting System, US funding to projects tagged with DHS descriptors decreased between 2017-2021. This decrease is also in line with a precipitous fall in funding for projects tagged with the gender marker.[8] As shown in Figure 3, US funding marked as principally for gender equality has been in decline since 2015. While funding marked as significant for gender equality slowly increased, 2021 saw a fall in both the gender equality and DHS markers. This trend could well turn around in 2022 and beyond—as in recent years US funding for gender equality has steadily increased based on 2022 and 2023 budget requests. Non-DHS funding has primarily been for Democracy Indicator Monitoring Surveys (DIMS) that capture public perceptions of various democratic norms and attitudes in Latin American countries. The remaining projects are mainly to support country-level capacity building by the US Census Bureau on family planning and reproductive health data collection and to support to health administrative systems.

Figure 3: US funding to gender equality and the DHS program

Source: ODW analysis of Clearinghouse for Financing Development Data dataset (Nov 2023) and OECD database “Aid projects targeting gender equality and women’s empowerment (CRS)” (Nov 2023)

- The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) is a top donor to gender data due to disbursements in 2018 and 2019 that supported its Medium Term Plan 2018-2021, specifically Strategic Objective 6: Technical quality, statistics and cross cutting themes (climate change, gender, governance and nutrition). The results framework for this objective calls for “data and analysis on all forms of malnutrition and support [for] the new areas of focus for The State of Food Insecurity in the World (SOFI); data on diets, disaggregated by gender; and data integration in support to the monitoring of comprehensive cross- sectoral policies.” In turn, the sub-section on gender mentions that “FAO will also continue to support the development, adoption, and monitoring of appropriate gender indicators related to food security and nutrition.” However, there is no guarantee that every dollar of these two disbursements will be directly channeled into gender data projects. No sizeable disbursements have been made since 2019.

- United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) remains one of the top donors for gender data but at a diminished scale, reducing disbursements by 20 percent between 2016-2018 and 2019-2021, while continuing its focus on birth registration and social protection programs. The decrease mirrors the overall decline in UNICEF disbursements for ODA, which fell by 40 percent from 2016-2018 to 2019-2021.[9] The reasons for this decline are unclear beyond the lack of significant administrative and budget support funds in the latter period. The link between this and a decline in funding for gender data cannot be established without additional information. UNICEF may fall further in the ranking of top donors due to the 2021 decision by the UK (one of UNICEF’s top 10 funders)[10] to cut funding by 60 percent, although it is not clear over what time horizon.[11] Early data shows that 2022 already saw a 16 million GBP decrease in funding from the UK.[12] Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) are crucial sources of gender data in many countries and are funded by government partners in collaboration with UNICEF and other development partners.[13]

- The Netherlands is a relatively new top donor for gender data, as shown in Table 1, with an increase of $15 million in disbursements since 2016-2018. In the first half of the 2010s, the Netherlands supported birth registration efforts in Bangladesh and Mozambique and Yemen’s 2014 Census. Between 2016-2018, the Netherlands supported Palestine’s 2017 census and census operations in Mali, culminating in the 2022 census. In the most recent period (2019-2021), the Netherlands continued to support census operations in Mali, but the biggest increase in funding has been to the Leading from the South program (Phase II 2021-2025), through which the Netherlands supports four regional women’s funds in Latin America, Africa, Asia, and indigenous communities that in turn fund women’s rights organizations to prevent and eliminate sexual and gender-based violence against women and girls, elevate women’s leadership and participation in (political) decision-making, and strengthen women’s economic empowerment and improve the economic climate for women. One of these funds, Fondo de Mujeres del Sur seeks “proposals that address research, documentation, data collection, evidence generation, as well as monitoring and evaluation aimed at accountability and advocacy.” An evaluation of Leading from the South says that this initiative aligns with the Dutch policy of Dialogue and Dissent by which the government supports civil society organizations and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ Dutch Policy on Women’s Rights and Gender Equality. This program is an example of how alignment between government policies at the highest level can result in support to projects that improve gender data at the country level, led by local organizations.

Canada, Sweden, and the United Kingdom are similar to the Netherlands in that they feature high-level commitments to gender equality in their domestic and foreign policy that are benchmarked using gender data. These high-level commitments are operationalized through strategies and mandates at the agency level Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) for example that guide project design and partnership agreements. Finally, these agencies routinely work on integrating a gender lens into their projects, for example gender toolboxes and gender help desks for staff at the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) and externally through international training programs on gender statistics.[14] Other donors can look to these practices to see if they have the fiscal and human capacity to reflect their gender equality ideals in more commitments to gender data.

POTENTIAL IMPACTS ON GENDER DATA

The shift toward loans for gender data funding, coupled with a decrease in grant-only support, raises concerns about exacerbating the already low availability of data for SDG5 on gender equality and for other gender-relevant SDG indicators, particularly in low-income countries where data gaps are greatest and loans are not possible.

The diminishing contribution from the United States and the limited increase in funding from top bilateral donors underscore the potential for even scarcer resources dedicated to gender data initiatives, posing challenges for monitoring progress on gender equality. While multilateral donors, including the World Bank, are major contributors, the scarcity of dedicated projects on gender data within their portfolios suggests a gap in addressing the specific data needs for SDG 5. The emphasis on regional and multi-country projects, as opposed to country-specific projects, must include low-income countries to meet the challenge of obtaining detailed gender data for SDG 5 in these countries.

Greater funding for population registers in recent years will hopefully improve the capacity for better birth and death registration for women and girls, ensuring greater legal rights and access to services. But the stark reality of less than one percent of all gender equality funding allocated to gender data compounds the struggle to enhance the availability of gender equality data. The small number of donors prioritizing such projects hinders comprehensive efforts to advance gender equality, especially in the most economically vulnerable regions. Donors must ensure greater coherence between their gender equality and data projects, either by ensuring that support to data systems is part of gender equality projects or that data for gender equality is an outcome of their data projects.

Though donors increased total funding for gender data in 2021 to pre-pandemic levels, those levels remain insufficient to plug the $500 million per year gap in financing needed for robust gender data systems. Donors may be able to pursue alternative funding modalities such as loans to make up the difference, but the lowest lift may be mainstreaming support to gender data into gender equality projects. If all donors to gender equality were modelled on countries like the Netherlands and allocated just one percent of their gender equality funding to gender data as well, the $500 million funding gap would be closed.[15]

CONCLUSION

This analysis has revealed several trends:

- Funding for gender data has increased, primarily driven by loans, while grants-only funding remains stagnant. Funding in future years will indicate the durability of this change from the World Bank and if other donors will begin using this funding mechanism.

- The list of individual countries receiving funding for gender data is short, and nearly half of the dollar value of funding goes to regional and multi-country projects.

- Very little gender equality funding goes to gender data, less than one percent on average. But donors vary widely on how aligned their gender equality and gender data funding streams are and how much of their financing for statistics is gender relevant.

- Funding for population registers has become the biggest individual activity funded by gender data financing in 2019-2021, compared with the prior ten years that focused more heavily on funding surveys, perhaps as an outcome of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Top bilateral donors show varied levels of financing for gender data, while the United States has witnessed a downturn in funding for statistics, gender data, and gender equality in recent years. In contrast, multilateral donors, led by the World Bank, have emerged as some of the largest contributors to gender statistics. New top donors to gender data and statistics include the Netherlands, FAO, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

These lessons all point toward the need for greater emphasis on statistical capacity by bilateral donors and ensuring low-income countries are not left behind. However, the increasing funding channeled through multilateral organizations may suggest that, as public goods, data and statistics and gender data may be most effectively funded by public institutions.

ANNEX

How do we know what we know about gender data financing?

- Bilateral, multilateral, and philanthropic donors report their activities on development financing to the OECD Creditor Reporting System (CRS). The OECD applies a methodology to standardize this reporting to enable sums across time and locations.

- Reporters fill out information regarding a project’s title and description as part of their reporting to Creditor Reporting System and multilaterals answer a survey on statistical projects.

- PARIS21 trains an algorithm to find data and statistics projects and further filters these projects for gender data relevance by keywords in titles and descriptions; the OECD gender or reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health markers; gender-relevant purpose codes; or UN Women as a channel. See PARIS21’s methodology note for further details.

Endnotes

[1] Filtered for where a project is flagged as gender data relevant (gend == TRUE).

[2] The prior high point was reached in 2019 at about $98 million.

[3] For an in-depth discussion of loan vs grant funding of aid to statistics, please see The Paris21 Partner Report on Sup- port to Statistics 2023. https://www.paris21.org/news/new-release-read-partner-report-support-statistics-2023

[4] Individual donor disbursements can be volatile due to low disbursement volumes in any given year. Due to this volatility, and to more accurately portray longer time trends, the subsequent analysis uses three-year totals.

[5] Note that Australia and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation appear on only one list each because they were top donors in one set of years but not the other.

[6] PARIS21. (2023). The PARIS21 Partner Report on Support to Statistics 2023, Page 16-17. https://www.paris21.org/sites/ default/files/media/document/2023-11/press-2023_0.pdf

[7] Commitments of $57 billion in 2020-2021. https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/develop- ment-finance-topics/development-finance-for-gender-equality-and-women-s-empowerment.htm

[8] Projects marked as principal are projects that started with an explicit focus on the policy target (gender equality in this case), whereas projects marked as significant are projects that contribute to the policy target incidentally. For more information about the OECD DAC gender equality policy marker, see here: https://www.oecd.org/dac/gender-development/dac-gender-equality-marker.htm

[9] https://stats.oecd.org/qwids/#?x=1&y=6&f=2:262,4:1,7:2,9:85,3:51,5:3,8:85&q=2:262+4:1,2+7:2+9:85+3:51+5:3+8:85+1:52+6:2016,2017,2018,2019,2020,2021,2022

[10] UNICEF. (2022). UNICEF Annual Report 2022, Page 31. https://www.unicef.org/media/141001/file/UNICEF%20Annu- al%20Report%202022%20EN.pdf

[11] UNICEF. (2021). UNICEF Statement on UK Funding Cuts. https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/unicef-statement- uk-funding-cuts

[12] House of Commons Library. (2023). UK Aid: Spending Reductions Since 2020 and Outlook from 2023. https://re- searchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-9224/CBP-9224.pdf

[13] UNICEF. FAQ. https://mics.unicef.org/faq#funding-and-cost

[14] Further details on Canada, Sweden, and the United Kingdom and their rationale for support for gender data can be found here: https://smartdatafinance.org/news/raising-support-for-gender-data-not-just-a-question-of-money

[15] $500 million funding gap divided by funding for gender equality total $58 billion in 2021 is about 0.9 percent.