OPEN DATA INSIGHTS:

EXAMINING THE CAPACITY AND RESILIENCE OF HEALTH DATA SYSTEMS

Edition December 2025

Photo: Shutterstock.com

Photo: Shutterstock.com

This brief is part of Open Data Watch’s Open Data Insights Series, which explores key topics in open data in greater depth, drawing on findings from the Open Data Inventory to support more effective and inclusive data systems. The primary authors were Jamison Henninger and Jay Ensor with inputs from the Open Data Watch team.

INTRODUCTION

In early 2025, abrupt reductions in official development assistance (ODA) exposed the fragile foundations of global health data systems. Dozens of national surveys were delayed or canceled; electronic medical records went offline; and long-standing monitoring programs were suddenly suspended. The disruption highlighted how dependent much of the world’s health data infrastructure remains on external financing.

Even before the aid reductions, these foundations were already under strain. Population-based data collection and routine administrative systems were increasingly delayed or underfunded: censuses slipped past the end of the 2020 round, major household survey programs such as the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) and Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) fell behind schedule, and persistent quality and financing gaps beset health management information systems (HMIS). As documented in Rebuilding Global Health Data: Scale, Risks and Paths to Recovery, many countries entered 2025 with limited capacity to absorb additional funding shocks.

This brief, part of the Open Data Insights series, draws upon results of the 2024/25 Open Data Inventory (ODIN) to examine the resilience of health data systems. Using the ODIN Health Index as a proxy for countries’ capacity to produce and publish health statistics, it examines how reliance on external financing affects the ability of national statistical systems to maintain regular, disaggregated, and accessible health data before and during the 2025 funding disruption.

Resilient health data systems are essential for implementing effective policies and responding to crises. Systems that can continue producing and releasing timely, accessible statistics during fiscal or operational shocks are better positioned to support planning, accountability, and progress toward the Sustainable Development Goals. The 2025 funding disruption demonstrated that systems dependent on external financing are less able to sustain regular, high-quality data collection when aid contracts, even where recent gains in data openness have been made.

THE ODIN HEALTH INDEX

The ODIN Health Index is a subindex of the full set of ODIN scores. It averages scores from four health-related statistical categories—Health Facilities, Health Outcomes, Reproductive Health, and Population & Vital Statistics—across two dimensions: coverage (whether data exist, are publicly available, how recent they are, and how much disaggregation and subnational detail they include) and openness (machine-readability; non-proprietary formats; download options; basic metadata; and licensing). The index summarizes countries’ capacity to produce and publish health data and is used in this brief as a proxy for health data system capacity.

Better ODIN Health Index scores are associated with better health outcomes. Across more than 120 low- and middle-income countries, higher ODIN Health Index scores are linked to higher life expectancy at birth, even after accounting for differences in GDP per capita. The association is modest but statistically significant: on average, countries with stronger capacity to produce and publish health data, as captured by the index, also have higher population life expectancy.

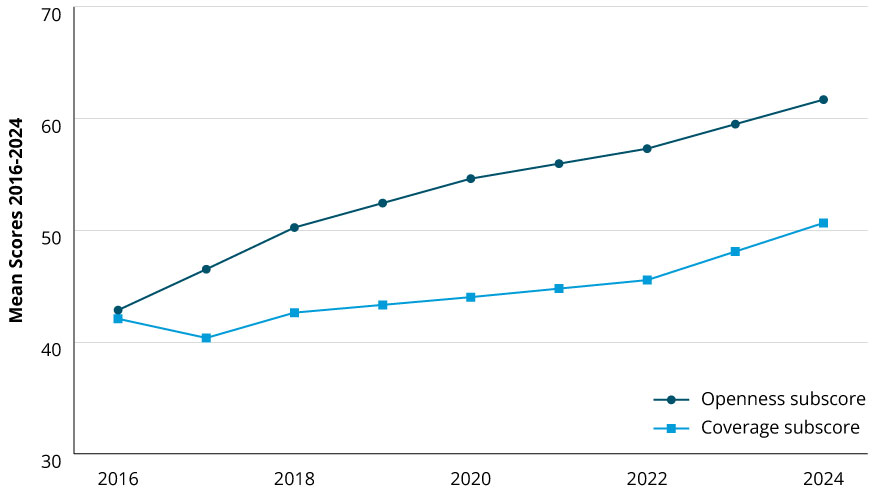

Figure 1 shows how average coverage and openness scores for the ODIN Health Index changed between 2016 and 2024. Both dimensions improved over this period, but openness rose faster than coverage. Coverage scores, which include increases in indicator availability and disaggregation, increased from 42.1 to 50.7 points out of 100 but were held back by limited progress on availability of subnational level data. Scores for second-level subnational data availability rose by only 3 points from a very low base. For health systems, this means that even where more indicators are available, data often remain too aggregated to guide targeted responses or equity-focused interventions.

Figure 1 Progress of ODIN Health Index, coverage and openness scores, 2016—2024

Source: ODW analysis of ODIN Scores

Source: ODW analysis of ODIN Scores

Openness improvements were greater and more widespread. Countries published more data in portals and under open licenses, making it easier for analysts and policymakers to reuse available data. By contrast, the publication of metadata changed little and remains one of the lower-scoring openness elements. Weak metadata signal gaps in statistical governance and standard setting that make it harder to align series across HMIS, civil registration and vital statistics (CRVS), and survey programs.

However, these averages hide substantial variation across countries. Between 2016 and 2024, 22 percent of countries increased their ODIN Health Index coverage score by more than 20 points, while scores of 13 percent fell, and openness gains were uneven across regions. Some health data systems moved toward more complete, timely, and open publication, while others remained static or fell behind. The country case studies that follow illustrate how similar financing environments can produce very different ODIN trajectories.

Overall, ODIN trends suggest that many countries entered 2025 with health data systems that were becoming more open but not consistently more current or granular. Systems were easier to access but still struggled to provide recent, subnational health statistics, the very characteristics that matter most when funding disruptions occur. This imbalance helps explain why the 2025 funding cuts translated so quickly into disruptions in data production and release.

FINANCING PATTERNS AND HEALTH DATA CAPACITY

External financial support for health systems has been a small share of total health spending in many countries. Over the period 2018 to 2022, data from WHO show the average share of external financing in countries’ current health expenditures was only 0.95 percent, but many poor countries are highly dependent on external support for their health systems. For countries classified by the World Bank as low income in 2020, 29.3 percent of their current health expenditures came from external sources.

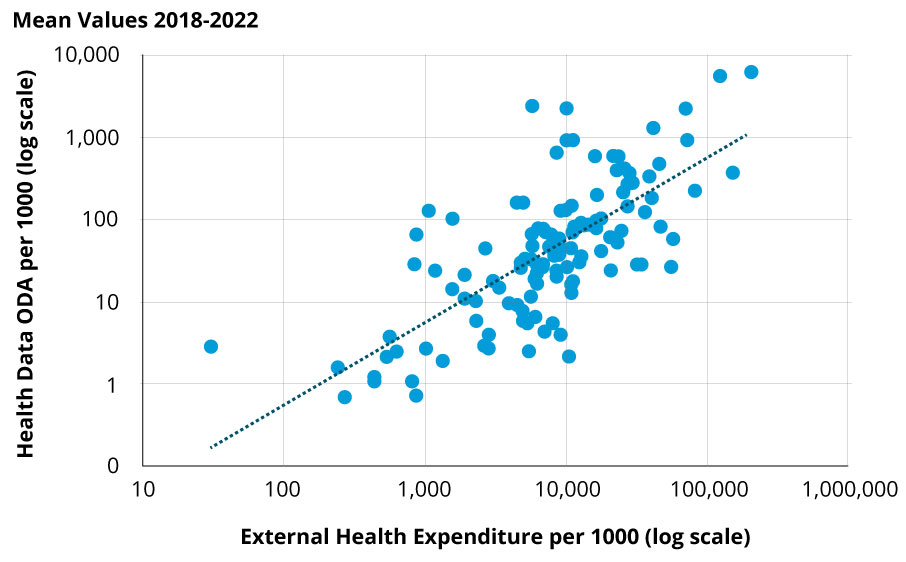

Only a small share of external financing for health reaches data production. Among countries that received any external support between 2018 and 2022, according to Open Data Watch analysis of data from the PARIS21 PRESS database, official development assistance (ODA) for health data systems received only 0.70 percent of total external support. For low-income countries, which received about one-third of ODA available for health data, the average annual amount received was less than 8 cents per person.

Figure 2 compares the country-level annual average ODA for health statistics per 1,000 residents with external support for health systems over the period 2018 to 2022. While health data ODA increases with support for the general health system, the amounts are several orders of magnitude smaller. The chart also shows the large range of support: at the low end, some low-income countries received less than 5 dollars per 1000 people; at the upper end, two small island developing states, Nauru and Tuvalu, received more than $5,000 dollars per 1,000 people.

Figure 2 External Health Financing vs. ODA for Health Statistics

Source: ODW Analysis of PRESS and WHO data

Source: ODW Analysis of PRESS and WHO data

Does support for health data systems follow overall spending on health systems? Table 1 shows the scores by quartiles for ODIN Health Index scores across the three assessment years. In the first (lowest) quartile, ODA for health data averaged $32.57 per 1000 residents and made up 0.90% of total external health spending. As countries’ ODIN Health Index scores rise, the absolute amount of ODA and its share of total external health expenditures falls.

Table 1: ODIN Health Index and external support for health and health data

(US dollars at 2022 price level; data for years 2018, 2020, 2022)

| Quartile | Average ODIN Health Index | Health data ODA per 1000 | External health expenditure per 1000 | Health data share of external expenditures |

| 1 | 27.8 | 32.57 | 3,628.53 | 0.90% |

| 2 | 35.4 | 25.08 | 4,359.01 | 0.58% |

| 3 | 41.3 | 14.84 | 2,492.56 | 0.60% |

| 4 | 48.3 | 10.69 | 2,602.91 | 0.41% |

Source: ODW Analysis of PRESS, WHO, and ODIN data

We cannot prove that donors are deliberately targeting countries with lower capacity for increased assistance. Nor can we show that their assistance has resulted in greater capacity and higher ODIN scores. There are large time lags and programmatic factors that determine whether aid for data systems is translated into greater capacity resulting in more useful, open statistics. Nevertheless, the results in Table 1 suggest that donors may have, at the margin, directed aid for data toward countries with greater need.

THE 2025 FUNDING SHOCK AND DATA SYSTEM DISRUPTIONS

The 2025 funding shock did not create new weaknesses so much as magnify existing ones. Health data systems that had long depended on external financing for core operations—survey fieldwork, HMIS upgrades, CRVS modernization—were the first to stall when donor programs paused or shifted. In many countries, data production slowed and releases were delayed, revealing how limited resilience translated quickly into operational disruption.

The largest disruption came from the suspension of U.S. assistance: nearly 90 percent of USAID’s health data contracts were frozen as part of a broader reallocation of foreign aid, including US $12.7 billion tied to health programs and data systems. But the impact extended beyond a single donor. Reductions in funding from the U.K.’s Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office, Global Affairs Canada, and several European Union development programs compounded the shortfall, particularly for survey operations and technical support for health information systems.

Major global data programs were affected. The DHS Program—funded by USAID since 1984 and active in 90+ countries—paused ongoing survey rounds and technical assistance in many settings while agreements remained in place and teams sought alternative financing. MICS—UNICEF’s flagship household survey program and a major source of SDG indicators—also came under budget pressure as UNICEF projected a sizeable funding shortfall, prompting reprioritization across country programs. In parallel, WHO reported funding-related disruptions to surveillance and health information systems, including laboratory networks—further slowing data processing and release and increasing the risk of breaks in time series used for HMIS and CRVS validation.

By mid-2025, many countries had scaled back routine HMIS reporting or paused updates, creating delays in validation and publication of key maternal, mortality, and coverage statistics. The cumulative effect was an information lag that weakened early-warning functions, routine planning, and accountability for national and global targets.

This disruption exposed core weaknesses in health data systems. Breaks in survey cycles and routine reporting reduced the availability and timeliness of health statistics, while limited subnational reporting constrained countries’ ability to target responses as conditions deteriorated. Systems that had made progress in publishing data openly but lacked stable financing for data production were less able to sustain regular, high-quality releases once external support contracted. The country case studies that follow examine how countries with similar exposure to the 2025 funding shock experienced different outcomes, reflecting differences in governance, coordination, and investment in core health data systems.

COUNTRY CASE STUDIES

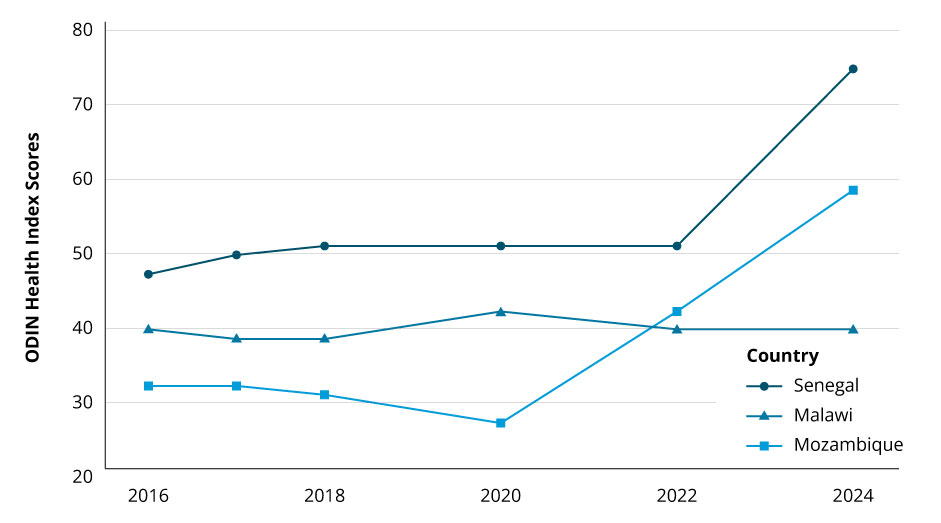

The country examples that follow show how governance and financing arrangements interact to shape the resilience of health data systems. Each case illustrates how similarly high levels of external support can yield very different outcomes depending on national leadership, planning, and coordination. Figure 3 shows the trajectories of ODIN Health Index scores for three countries: Senegal, whose scores rose sharply after 2022; Mozambique, which has shown steady improvement since 2020 after a dip in earlier years; and Malawi, where performance has largely stagnated despite very high levels of external funding.

Figure 3 ODIN Health Index scores for case study countries

Source: ODW Analysis of ODIN Scores

Source: ODW Analysis of ODIN Scores

Senegal (high ODIN Health Index score)

External sources financed about 19 percent of Senegal’s health spending over the past decade—placing it near the bottom of the top third of all LMICs. Over the same period, its ODIN Health Index rose from 50 in 2022 to 74 in 2024, driven by sharp gains in openness across all health categories and moderate improvements in coverage, especially for Health Facilities and Reproductive Health. Senegal illustrates how a country with significant external funding can achieve strong and broad progress when partner resources are aligned with government-led plans for core health data systems.

Senegal’s national statistics strategy emphasizes modernization of statistical infrastructure and digital transformation, and clarifies roles for coordination between the national statistical system and sector ministries. In the health sector, the Planning, Research and Statistics Directorate coordinates statistical production with other directorates and the national statistics office, supported by a Health System Strengthening Platform that brings together government and partners. The National Health and Social Development Plan 2019–2028 pairs external financing with domestic resources through program budgets and an annual results framework, assigning responsibilities and budgets to units leading HMIS and civil registration and vital statistics (CRVS) so that partner funding reinforces these priorities rather than stand-alone projects.

Core systems have been built out around this framework. The HMIS uses standardized tools, a unified reporting calendar, and routine data-quality checks (for completeness, timeliness, and internal consistency), supported by a national facility list that enables regular district-level analysis. CRVS digitization is being expanded to improve timeliness and linkage with health records, while household surveys are scheduled in multi-year plans that maintain sampling frames and define handoffs to HMIS teams for indicator reconciliation. Capacity-building and regular data-use sessions are embedded in sector performance reviews, strengthening day-to-day use of statistics in management. Together, these choices help explain Senegal’s ODIN gains: more regular publication, better-documented and more open datasets, and stronger subnational reporting, with external finance anchored in a coherent, government-led system.

Mozambique (medium ODIN Health Index score)

External sources financed an average of 58 percent of Mozambique’s health spending over the period 2018–2022—3rd highest among 134 LMICs and 2nd among 52 African LMICs. ODIN Health Index performance has been mixed but ultimately positive: the overall score fell from 31 (2016) to 26 (2020), then climbed to 58 (2024). Most of the recent gains reflect stronger and more openly available reproductive-health data and broader improvements in openness. Mozambique is therefore a case where a highly aid-dependent system has moved into the middle of the ODIN distribution, with openness improving faster than coverage.

Mozambique’s statistical system is constrained by outdated legislation and weak coordination across ministries and development partners, leading to parallel reporting systems, limited feedback, and uneven data quality. These issues are explicitly acknowledged in the National Strategy for the Development of Statistics 2025–2029, which calls for updating the statistical law and strengthening inter-institutional coordination. Routine health data show similar weaknesses: a 2022/23 assessment found that only 9 percent of records in the health management information system (HMIS) exactly matched paper registers, with capacity particularly weak at provincial and district levels, findings that underpin the Ministry of Health’s Data Quality Improvement Plan 2025–2029. That plan proposes measures to strengthen coordination for health information systems, standardize instruments and validation processes, and expand training, supervision, and routine data-quality audits.

Together, these assessments and plans codify the structural problems that have held back data coverage, while setting a direction for reform that goes beyond the openness gains already reflected in ODIN. Until the legal updates and coordination mechanisms are fully in place and consistently applied below the national level, Mozambique’s ODIN coverage elements are likely to improve more slowly than openness, and the health data system will remain exposed to funding shocks in the near term.

Malawi (low ODIN Health Index score)

External sources financed an average of 59 percent of Malawi’s health spending over the period 2018–2022—2nd highest among 129 LMICs and the highest among 51 African LMICs. Despite this, ODIN Health Index performance has remained low and largely flat from 2016 to 2024. The headline stability masks movement underneath: between 2022 and 2024 the coverage score fell by 7.5 while openness rose by 7.5, driven mainly by openness gains in Population & Vital Statistics and smaller declines in coverage across other categories. Taken together, Malawi illustrates that heavy external financing does not automatically translate into stronger, more regular health statistics without institutional and governance reforms to channel funds toward data production and use.

Malawi’s statistical system is characterized by weak central coordination, duplicative releases, inconsistent standards, uneven administrative data quality, and staffing and ICT gaps across ministries and departments; these problems are laid out in the National Statistical System Strategic Plan 2019/20–2022/23. In the health sector, tight fiscal space coincides with a heavy and fragmented donor footprint, with external resources executed through hundreds of financing channels and implementing partners, a pattern the Health Sector Strategic Plan III 2023–2030 highlights as a major obstacle to coherent investment in core information systems. The National Digital Health Strategy 2020–2025 sets out a standards-based approach to digital health, including interoperability and a national Master Health Facility Registry, but implementation has been uneven and coverage remains incomplete.

Malawi has taken concrete steps—an interoperability architecture, a facility registry, and costed statistical activity plans—yet system-wide governance and coordination gaps persist, and day-to-day HMIS quality and subnational data coverage remain uneven. That mix aligns with Malawi’s ODIN pattern: improvements in openness outpacing coverage and a health data system that remains highly vulnerable to funding shocks and further stagnation if external support shifts or declines.

POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS AND CONCLUSIONS

The 2025 funding crisis confirmed that short-term, project-based aid cannot replace durable national investment. Even as ODIN Health Index scores rose, many countries remained exposed to shocks because their data systems were built on unpredictable external financing. Transparent, routine tracking and publication of financing flows to health data systems—both domestic and external—are essential for understanding how resources move through the system, identifying gaps, and supporting smarter alignment between partners and national priorities. Without visibility into these flows, countries and donors alike cannot ensure that investments strengthen the long-term sustainability and resilience of data systems rather than reinforcing short-term project cycles. Strengthening resilience for these systems will require policies that:

- Protect core data programs.

Commit multi-year funding for censuses, DHS/MICS, CRVS operations, and routine HMIS. Cover fieldwork, system maintenance, and data processing, so cycles continue even when budgets tighten. - Align external financing to country plans and co-finance.

Route partner funds through government strategies and budget lines (NSDS and health plans), with domestic cost-sharing and annual reviews. Co-financing should prioritize operating costs and scheduled upgrades that keep systems running and resilient, consistent with country plans. - Invest in interoperability and accountability.

Create national registries (facilities, clients, terminology), adopt open standards and institutionalize data-quality audits, and define clear roles for the NSO and Ministry of Health to reduce parallel reporting and improve subnational coverage. - Invest in staffing, skills, and data use—not just tools.

Fund multi-year posts and ongoing training for statisticians and HMIS officers; embed supervision and data-quality audits; and require publication standards (open licensing, documentation) so data are used in planning and budgeting. - Set measurable goals and monitor them

Increased capacity does not happen overnight. Realizing returns on new investments in statistical infrastructure, standards, and staff skills will require time and sustained efforts. By setting realistic goals linked to the regular production, timeliness, and publication of health data and reviewing them routinely, managers can better ensure that investments yield sustained improvements not just short-term gains.

Together, these measures shift countries from emergency-driven data cycles toward stable, resilient systems that support long-term planning and accountability. ODIN’s results are more than a snapshot of openness; they are an early signal of system capacity. As priorities realign after 2025, sustained investment in national data systems will be needed to restore confidence in global health statistics and keep progress toward the SDGs on track.