OPEN DATA INSIGHTS:

BUILDING MARKET CONFIDENCE THROUGH BETTER DATA

Edition July 2025

Photo: NicoElNino/Shutterstock.com

Photo: NicoElNino/Shutterstock.com

This brief is the first of Open Data Watch’s Open Data Insights Series, which explores key topics in open data in greater depth, drawing on findings from the Open Data Inventory to support more effective and inclusive data systems. It was primarily authored by Hakim Moghaddami with inputs from the Open Data Watch team.

INTRODUCTION

This brief examines how the coverage and openness of economic and financial statistics are linked to stronger investment climates. Coverage and openness are measured using the Open Data Inventory (ODIN) alongside adherence to international statistical standards, then compared to key investment indicators such as sovereign risk ratings and capital flows. Positioned within the broader context of financing for development, the analysis indicates that investments in national statistical systems (NSSs) can foster environments more conducive to private-sector engagement. That effect is strongest when those investments both boost data production and prioritize user-centric dissemination. While the brief does not attempt to prove a cause-and-effect relationship, it examines patterns and insights that suggest how stronger data systems, rooted in comprehensive reforms and broader governance improvements, might support better investment outcomes.

To explore these associations, the brief draws specifically on ODIN’s Economic and Financial Statistics subscore, which assesses 197 countries on the availability and openness of key datasets relevant to economic planning and financial analysis. As one of three categorical subscores in ODIN (the others are Social Statistics and Environment Statistics), Economics and Financial Statistics subscore measures:

- Coverage: How complete are a country’s data offerings for seven categories on indicators encompassing national accounts, labor, price indexes, government finance, money and banking, international trade, balance of payments.

- Openness: How well do a country’s data offerings meet international standards of openness considering:

- Open and machine-readable data formats

- Data download options that enable better access

- Metadata completeness

- Open licensing

Over the past decade ODIN has become a vital tool for identifying data gaps. Although the 2024/25 report finds significant progress towards more open and comprehensive data systems, this progress is not guaranteed. Without continued investment and institutional commitment, the advances remain fragile, posing a risk to the data infrastructure that is essential for sustainable development and economic planning.

HOW DATA SYSTEMS INFLUENCE MARKET CONFIDENCE

While private firms routinely rely on macroeconomic indicators to evaluate market risks and opportunities, they often overlook the systems producing them. Adherence to the standards of the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) data dissemination bulletin board (DSBB) and tools such as ODIN and the World Bank’s Statistical Performance Indicators (SPI) provide investors information on the quality and accessibility of a country’s economic and financial data. Rather than merely supplying numbers, these systems help structure and standardize raw data, which can contribute to informed decision-making.

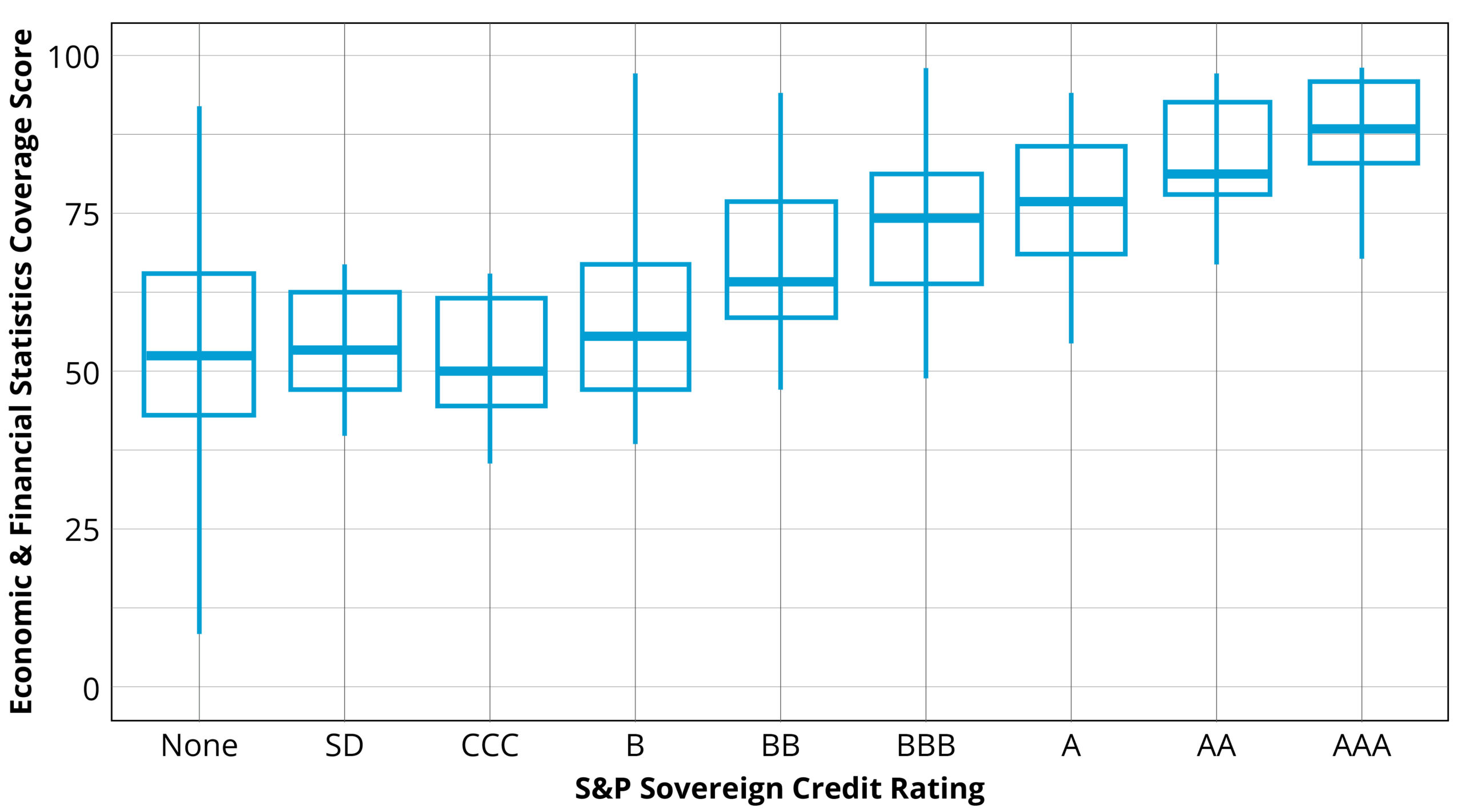

Figure 1 illustrates this relationship in greater detail, using a box plot to show how ODIN Economic and Financial Statistics coverage scores vary by sovereign risk rating. In each rating group (e.g., A, BBB, BB), the box shows the middle 50 percent of scores, with the line inside the box representing the median. The “whiskers” extend to the minimum and maximum scores within a typical range, and any dots outside those lines indicate outliers.

Countries with stronger credit ratings tend to have higher and less variable coverage scores, while lower-rated countries often show lower scores and wider variation. This visual pattern reinforces the association between robust statistical systems and more stable investment environments. This suggests that markets implicitly reward robust data systems even when investors don’t explicitly evaluate statistical capacity. Indeed, it was a premise of the DSSB’s creation that public information about the compilation and availability of economic and financial data would reduce market uncertainty. Although outliers exist—where strong data coexist with lower investment ratings due to other factors like political instability or infrastructure gaps—the correlation reinforces the idea that statistical capacity is foundational, though not solely determinative, for attracting higher levels of private investment.

Figure 1: Economic and Financial Statistics Coverage by Sovereign Risk Ratings (2024-25)

Box plot key: The median (line inside of box) represents the typical ODIN score for each rating tier. The box spans the interquartile range (middle 50% of scores), while whiskers show the data’s typical range. Outliers (e.g., AA or CCC rated countries) are marked by separate points.

Figure 1 represents the S&P Sovereign Credit Ratings of 197 countries as of April 10, 2025 (https://disclosure.spglobal.com/sri/) mapped against ODIN 2024/2025 Economic and Financial Statistics Coverage scores. 128 countries had ratings of SD and above, the remaining 69 countries assessed by ODIN have been assigned a rating of None by the authors.

Global financial reforms–including those under discussion at the 2025 Fourth International Conference on Financing for Development (FfD4)–offer a timely opportunity to position national statistical systems as foundational components of investment infrastructure. The World Bank’s Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) noted in 2018 that countries adopting a systemwide approach to statistical capacity building–combining legal and institutional reforms with investments in human and physical infrastructure—achieved significant success. Yet, many countries continue to face substantial data gaps and are seeking longer-term, better coordinated support from multilateral institutions that FfD4 aims to prioritize–support that could strategically be used to strengthen national statistical systems. While progress has been uneven, improving data quality and openness remains a crucial step to mitigate uncertainty, ensure macroeconomic stability, and build public trust.

Although statistical capacity (measured through tools like ODIN) is positively associated with better investment climates, data alone cannot overcome deeper determinants of capital flows—such as regulatory quality, political risk, and global economic conditions. The relationship is foundational, not deterministic: even the best statistical systems can’t attract capital if broader institutional conditions are weak.

PRIVATE SECTOR USES OF ECONOMIC DATA

Economic and financial data play an essential role in private sector decision-making as investors and multinationals use data to:

- Assess exchange rate volatility and sovereign debt sustainability

- Monitor macroeconomic trends for forecasting and scenario planning

- Evaluate a country’s regulatory and operating risk

In 2024, the World Bank pledged to increase the availability of high-frequency, policy-relevant data to aid investor confidence in developing countries. Firms rely on labor force participation, inflation, trade flows, and taxation statistics to price risk and identify market entry strategies. Countries with robust data ecosystems that prioritize transparency can reduce due diligence costs and-as demonstrated by past research—attract significantly more Foreign Direct Investment (FDI).

The Global Investment Competitiveness Report 2019/2020 further reinforces this message, showing that regulatory risk is among the top concerns for investors, often more so than cost-related factors. Countries with more predictable and transparent regulatory frameworks have measurably higher FDI inflows and lower investment risk. As the report explains, investors are more likely to reduce or withdraw investments in response to legal and regulatory uncertainty. This underscores the importance of accessible, reliable data in reducing investor uncertainty and improving risk assessments.

Dependable macroeconomic and fiscal data are foundational to these assessments. For instance, S&P Global’s Sovereign Risk Indicators (SRI) utilizes measures such as government debt levels, current account balances, and inflation rates to assess a country’s creditworthiness. Inconsistent or inaccessible data can weaken these evaluations, leading to higher risk premiums or diminished investor confidence.

Another important source of financial inflows is net portfolio equity investment, which tracks foreign purchases of domestic equity securities. Alongside FDI, it serves as a barometer of investor confidence and market appeal. These flows are often highly sensitive to governance and transparency risks—including data openness, a core feature of ODIN’s evaluation framework.

DISSEMINATION STANDARDS AND OPENNESS AS MARKET SIGNALS

Participation in international data standards is a critical indicator of a country’s transparency and reliability in global markets. The IMF’s international dissemination standards including e-GDDS, SDDS, and SDDS+ represent formal commitments to open and timely data sharing.

A 2021 World Bank blog noted that countries adopting international statistical standards tend to benefit from lower borrowing costs and greater access to capital markets. This link is reinforced by evidence from an IMF working paper (2022), which found that countries joining the SDDS or GDDS frameworks experienced cumulative reductions in sovereign bond spreads of up to 14 percent within three quarters, underscoring the role of data transparency in bolstering market confidence. However, meeting these standards remains particularly challenging for low-income countries, as they frequently face limitations in both technical capacity and sustainable funding.

ODIN adds value by complementing IMF frameworks. While IMF standards emphasize dissemination formats and frequency, ODIN evaluates both what data are available (coverage) and how accessible (openness) they are across essential economic domains such as national accounts, prices, labor, and government finance. As such, ODIN offers a broad and accessible measure of a country’s statistical transparency that is particularly useful for comparing data environments across countries regardless of their participation in formal standards. This relationship is evident in Figure 11 of the ODIN 2022 Biennial Report, which shows that SDDS and SDDS+ countries consistently outperform e-GDDS and non-subscribers in ODIN’s Economic and Financial Statistics category.

Taken together, participation in IMF data standards and strong ODIN performance serve as complementary signals of institutional quality, transparency, and governance—factors that play a central role in shaping investor confidence and risk assessment.

COUNTRY CASE STUDY: ODIN AND PRIVATE INVESTMENT

To further explore the link between statistical systems and investment climates, we can look at three countries—Ghana, Uzbekistan, and India—examining overall ODIN Economic and Financial scores alongside complementary indicators such as Statistical Performance Indicator (SPI) scores, participation in the IMF dissemination standards (e-GDDS/SDDS), S&P Sovereign Risk Ratings (SRI), trends in FDI, and net portfolio equity inflows. Notably, ODIN scores are not only correlated with SPI scores—they are an input to them: ODIN’s openness sub-score feeds into SPI’s assessment of data accessibility (Pillar 2), while subnational coverage informs SPI’s measure of geospatial data availability (Pillar 3).

Table 1. Selected Country Indicators Linking Statistical Capacity and Investment Trends (2017–2024)

| Country | GHANA | UZBEKISTAN | INDIA |

| e-GDDS/SDDS Status | e-GDDS | e-GDDS | SDDS |

| ODIN Economic and Financial Score (0 – 100) | 45 → 72 | 23 → 85 | 57 → 63 |

| SPI Score (0 – 100) | 62.33 → 67.91 | 42.63 → 80.33 | 64 → 73.6 |

| SRI Rating | SD | BB- | BBB- |

| Net FDI Trend | 2.99B (2018) | 624M (2018) | 42.12B (2018) |

| Net Portfolio Equity Inflow | -40.4M → -9.3M | 3.1M → 23.1M | -4.36B → 21.43B |

Ghana, Uzbekistan, and India were chosen as illustrative cases representing various statistical capacities and reforms across distinct economic contexts. In the discussion below, each country is assigned to a broad category to suggest how statistical improvements align with investment performance. These categories are not prescriptive but help clarify how statistical progress interacts with institutional and economic realities.

1. Uneven Statistical Progress with Mixed Investment Signals

India illustrates the risks of stagnation within a mature statistical system. Despite subscribing to the IMF’s SDDS since 1996, its ODIN Economic and Financial score improved only modestly between 2017 and 2024 (from 57 to 63). This improvement was uneven as the coverage subscore rose significantly (51.9 to 61.5) while the corresponding openness subscore has declined from its 2022 peak (68.6 to 64.3 in 2024). This divergence between coverage and openness–where more data are published but less accessible–points to potential inconsistent data sharing policies or shifting political priorities.

During the same period, India has invested in digital infrastructure and expanded the use of administrative data, signaling modernization in production systems. However, volatility in FDI and portfolio flows suggests that improvements in coverage alone are not sufficient to sustain investor confidence.

Even high-quality statistics will fail to translate into actionable insights for policymakers and market confidence if they are not published in accessible, timely, and user-friendly formats. In high-capacity systems, sustained attention to openness remains essential for reinforcing trust in official data.

2. Rapid Statistical Reforms Coincide with Rising Investment

Uzbekistan shows how statistical improvements, backed by donor support and policy reform, can contribute to favorable investor sentiment and increased private flows. Since adopting e-GDDS in 2018, the country’s ODIN Economic and Financial score rose sharply from 23 to 85, and its SPI score increased from 36 to 80.33. These gains align with significant growth in both FDI inflows (from $624M in 2018 to $2.16B in 2023) and net portfolio equity inflows (from $3.1M to $23.1M between 2017 and 2023). This suggests that when statistical reforms are part of a wider modernization effort, they can enhance credibility and attract capital.

These parallel trends suggest that statistical reforms were part of a larger strategy to increase transparency and modernize public institutions. With support from international partners, Uzbekistan has improved data coverage and accessibility—signaling reliability to external markets and reducing the perceived risk for private capital.

While other governance and economic factors also play a role, Uzbekistan’s case demonstrates how rapid, well-supported improvements in statistical capacity can reinforce investor confidence, particularly in countries seeking to reposition themselves in global capital markets.

3. Statistical Progress Outweighed by Macroeconomic Risk

Ghana has made significant strides in statistical transparency, boosting its ODIN Economic and Financial score from 45 to 72 and SPI score from 59 to 67.91 since 2016, while maintaining its e-GDDS compliance. These improvements reflect a clear institutional commitment, supported by donor engagement, to enhance the coverage and accessibility of economic and financial data.

However, despite these gains, investment conditions worsened. FDI fell 56 percent ($2.99B to $1.32B), the country experienced a sovereign default (SD rating), and portfolio flows remained persistently negative (-$9.3M in 2023). This disconnect emphasizes that while strong data systems are foundational, they cannot alone overcome macroeconomic instability and debt sustainability concerns—factors that continue to deter potential investment despite statistical reforms.

STRATEGIC IMPLICATIONS FOR FINANCING FOR DEVELOPMENT

Improved data alone do not guarantee increased investment. However, statistical capacity—as measured by ODIN—is closely associated with stronger investment climates. ODIN can also provide a framework for identifying data gaps and setting priorities for investments in data systems that support market confidence. Following the Fourth International Conference on Financing for Development, there is a timely opportunity to elevate the role of data in advancing sustainable finance goals. Open and well-governed data ecosystems can enhance risk pricing, lower investor uncertainty, and bolster the legitimacy of national plans.

As noted by Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data, “we won’t fill the SDG financing gap without strong data and statistical systems.” Robust data infrastructure is not a luxury, but a prerequisite for mobilizing private capital and achieving long-term development goals. By investing in such systems, countries can unlock not only development outcomes, but durable economic opportunities for years to come.